Modern military equipment and weapons of the Russian army. Promising and latest weapons of Russia: missile, anti-tank, small arms. Pistols for the army

Painting by Russian artists

Painting by Vasily Surikov "Morning of the Streltsy Execution". Canvas, oil, canvas size 218 × 379 cm. The young artist’s move to the “first throne”, impressions of ancient Moscow architecture (whose monuments, as he later told M. A. Voloshin, looked “like living people”) were an important incentive on the way to his first historical masterpiece - the painting "Morning of the Streltsy Execution". The artist, according to the same Voloshin, "realized from the forms", painted what he saw, possessing an amazing ability to open the historical and poetic aura of external visibility. Therefore, when he said that "Sagittarius" was born from the impression of a "burning candle on a white shirt", and "Boyar Morozova" - from a "crow in the snow", then this, of course, sounds like an anecdote, but at the same time affects the most the nerve of the master's creative method.

O personal impressions Surikov wrote: “It started here, in Moscow, with me something strange. First of all, I felt more comfortable here than in Petersburg. There was something much more reminiscent of Krasnoyarsk in Moscow, especially in winter. And, like forgotten dreams, pictures of what I saw in childhood, and then in my youth, began to rise more and more in my memory, types, costumes began to be remembered, and I was drawn to all this, as to something dear and inexpressibly dear. But the Kremlin with its walls and towers captured me the most. I don’t know why myself, but I felt in them something surprisingly close to me, as if I had known them well for a long time. As soon as it began to get dark, I ... set off to wander around Moscow and more and more to the Kremlin walls. These walls have become a favorite place for my walks at dusk. And then one day I was walking along Red Square, not a soul around ... And suddenly the scene of the archery execution flashed in my imagination, so clearly that even my heart began to beat. I felt that if I write what I imagined, then an amazing picture will come out.

Over the years of work on the canvas “Morning of the Streltsy Execution”, huge changes have taken place in Surikov’s life. He managed to get married, two daughters were born in the family - Olga and Elena. His wife Elizaveta Avgustovna Share was French on her father's side, and on her mother's side she was a relative of the Decembrist Svistunov. They met back in St. Petersburg in the Church of St. Catherine on Nevsky Prospekt, where they came to listen to organ music. While working on the murals in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, Vasily Ivanovich often came to the capital, met with Elizaveta Avgustovna, was introduced to her father August Chara, the owner of a small paper trade enterprise. The artist was not carried away by work in the temple, he dreamed of finishing it as soon as possible, becoming financially independent and getting married. The wedding took place on January 25, 1878 at the Vladimir Church in St. Petersburg. From the groom's side, only the Kuznetsov and Chistyakov families were present. Surikov was afraid of his mother's reaction to the news of his marriage to a Frenchwoman and did not inform his relatives in Krasnoyarsk about the wedding.

The young settled in Moscow. The painter went headlong into work on the painting “Morning of the Streltsy Execution”. He was finally free from material worries, household chores were taken over by his wife. However, in everyday life Vasily Ivanovich was always unpretentious and simple. For several years, Surikov did not write anything extraneous. The captivating idea of the picture completely filled all his thoughts. Once upon a time, one image sunk into his memory, striking like a tragic allegory: a candle lit during the day is a sad symbol of funeral and death. He worried Surikov for many years, until he connected with the theme of the massacre of the archers. Dim in the gray air of a gloomy morning, the light of a candle in a still living hand was associated with execution. The architectural environment of the Execution Ground near the Kremlin suggested the basis for the multi-figure composition, and the images of archers and many candles became its key components.

An amazing picture is thoroughly permeated with symbols. An extinguished candle is an extinguished life. The inconsolable woman in the foreground presses the extinguished candle of the already executed archer to her head. Next to her, a barely smoldering candle of the one who is being taken away to execution is thrown into the mud. The soldier in the center has already taken the death candle from the grey-haired bearded man and is blowing it out. The rest of the candles still burn evenly and brightly.

The central storyline of the picture and its main emotional core is the opposition of archers to royal tyranny. The most symbolic is the image of a red-bearded soldier. His hands are tied, his legs are chained in stocks, but the irreconcilable gaze blazing with hatred beats through the entire space of the picture, colliding with the angry and equally implacable gaze of Peter. The foreigners depicted on the right, while calmly watching what is happening, but then they will describe in horror how the Russian autocrat himself acted as an executioner. Peter personally cut off the heads of five rebels and one clergyman who blessed the rebellion with an ax, and executed more than eighty archers with a sword. The tsar also forced his boyars to participate in the cruel massacre, who did not know how to handle an ax and caused unbearable torment to the condemned by their actions. Surikov read about all this in the diary of the secretary of the Austrian embassy Korb, an eyewitness to the events.

But there are no bloody scenes in the picture itself: the artist wanted to convey the greatness of the last minutes, and not the execution itself. Only a lot of red details of clothing, as well as the crimson silhouette of the Intercession Cathedral, towering over the Toyota of convicted archers and their families, reminds the viewer of how much blood was shed on that tragic morning.

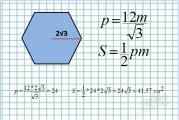

The architectural design of the canvas is very important. The tower of the Kremlin standing alone corresponds to the lonely figure of the king; the second, the nearest tower, unites into one whole a crowd of observers, boyars and foreigners; the even formation of the soldiers exactly repeats the line of the Kremlin wall. The artist deliberately moved all the buildings to the Execution Ground, using the compositional technique of bringing plans closer together and creating the effect of a huge crowd of people. The cathedral continues and crowns this crowd of people, but the central dome of the Church of the Intercession of the Virgin did not seem to fit into the space: it is “cut off” by the upper edge of the picture and symbolizes the image of Russia, beheaded by Peter I. The remaining ten domes correspond to the ten depicted mortal candles.

The latter are clearly not randomly located in accordance with strict geometry. Four bright lights lie exactly on one sloping line starting from the lower left corner (in the hand of a person sitting with his back to us), passing through the candle flame of the red-bearded and black-bearded archers to the suicide bomber standing at the top and bowing to the people. But if, through a candle located on the canvas above the others in the hands of a standing archer, a straight line is drawn, directed downward - to the one that burns out in the mud, then this line will also connect the three flames, passing through the light blown out by the soldier. Thus, a strict cross is clearly manifested, as if crushing a crowd of doomed rebels. Three other, less noticeable candles, located in the background of the composition (on the left under the arc, in front of the archer standing at the top and immediately behind him), are also located on the same line, actually dividing the canvas in half. It is crossed along a strict perpendicular by a straight line drawn between the upper candle and the extinguished one. In total, there are three regular crosses on the cartan. The third is formed by the intersection of the “line of will and opposition” (from the eyes of the king to the eyes of the red-bearded archer) and the one that goes from the extinguished candle to the quiet light in the background, below the face of the standing archer.

All of Surikov’s work is characterized by an amazing concern for those who come to look at his paintings: “I had the idea not to disturb the viewer, so that there would be peace in everything ...”, he said about his Sagittarius. Despite the horror of the transmitted historical event, the artist tried to depict the tragedy of human destinies as restrained as possible. No outward pretentious showiness and theatricality, no raised axes, hands raised to the sky, bloody clothes, hangmen and severed heads. Only the deep drama of national grief. You don’t want to turn away from this picture with a shudder, on the contrary, looking at it, you are more and more immersed in the details, you empathize with its heroes, acutely understanding the cruelty of that time.

The canvas "Morning of the Streltsy Execution" was exhibited at the Ninth Traveling Exhibition in March 1881. Even before its discovery, Ilya Repin wrote to Pavel Tretyakov: “Surikov’s painting makes an irresistible, deep impression on everyone. All unanimously expressed their readiness to give her the most the best place; it is written on everyone's faces that she is our pride at this exhibition... Today she is already framed and finally placed... What a prospect, how far Peter has gone! Mighty picture! Tretyakov immediately purchased this ingenious historical work for his collection, paying the master eight thousand rubles.

But March 1, 1881 was marked by another event that constituted a mystical counterweight to the theme of reprisals against rebels. On the opening day of the exhibition, in which the central place was occupied by a painting depicting the execution of archers by Tsar Peter I, the Narodnaya Volya committed a terrorist act, cracking down on Emperor Alexander II.

Surikov Gor Gennady Samoilovich

V. "MORNING OF THE STRELETSKY EXECUTION"

V. "MORNING OF THE STRELETSKY EXECUTION"

The event depicted by Surikov in his first large picture - "Morning of the Streltsy Execution", marked a turning point in the new Russian history.

In the village of Preobrazhensky in October 1698 and at Lobnoye Mesto, the recalcitrant pre-Petrine Russia, defeated by the great reformer, was dying. “...Peter accelerated the adoption of Westernism by barbarian Russia, not stopping at barbaric means of struggle against barbarism,” wrote Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, revealing the essence of Peter's executions carried out in the name of the future of Russia.

Peter was in the "great embassy" in the West and lived in Vienna, when disturbing news came from Moscow: four streltsy regiments, sent after the Azov campaign to the western border, rebelled and went to Moscow to enthrone Princess Sophia.

The archers were exhausted by the heavy and long siege of Azov, excited and dissatisfied with non-payment of salaries and harassment. Their discontent was skillfully taken advantage of by the circles of the reactionary boyars, grouped around Princess Sophia, by that time already imprisoned in the Novodevichy Convent, and her relatives Miloslavsky. Sophia herself gave the signal for a rebellion, sending a “pompous” letter to the archers with a call to take Moscow from the battle.

V. Surikov. Study for "The Morning of the Streltsy Execution" (a red-haired archer in a hat) (TG).

V. Surikov. Study for "Morning of the Streltsy Execution" (an old woman sitting on the ground) (TG).

Boyar demagogy deceived the archers. But it would be a mistake to reduce the whole meaning of the streltsy revolt to boyar intrigues.

The archers rose not only because they were deceived by the generous promises of Sophia and the Miloslavskys, not only because they became impoverished without a salary and did not want to be separated from Moscow and their families, leaving for a long time to the Lithuanian border. The streltsy movement reflected the hopes and aspirations of the oppressed, tormented, suffering people, who had to endure the historically progressive cause of Peter on their shoulders.

In a class society, progress is made at the expense of the oppressed. Such is the inexorable logic of history, such is its fundamental internal contradiction. Peter led Russia to a new, progressive path, but the great reforms were bought at the price of the people's blood and the unheard-of cruel enslavement of the masses.

Having opposed Peter and his innovations, the archers knew that the people sympathized with them, and they drew from the people's support the consciousness of their rightness.

Peter, having received news of the rebellion, gave a decree to his governor, Prince Romodanovsky, to mercilessly destroy the rebels, and he himself immediately left for Moscow. But the rebellion was crushed before his arrival. In June 1698, near New Jerusalem, the Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky regiments met the archers under the command of the boyar Shein and General Gordon. Streltsy could not withstand the onslaught of regular troops and surrendered ...

On the "search" of Shane, 136 archers were hanged, 140 were beaten with a whip and about 2 thousand were sentenced to deportation to different cities. Peter, returning to Moscow, was dissatisfied with the "search", ordered to reconsider the whole case and personally led the investigation. The organizational role of Sophia became clear. The Streltsy army was destroyed. Sophia was tonsured a nun. Mass executions began. There was not a single square in Moscow where scaffolds and gallows with hanged archers did not stand. The opposition to the Petrine reforms was drowned in the blood of the archers.

“Surikov passionately loved art, always burned with it, and this fire warmed around him both the cold apartment and his empty rooms, which used to be: a chest, two broken chairs, always with holes in the seats, and a palette lying on the floor, small, very sparingly soiled with oil paints, immediately lying around in skinny tubes, ”says Repin.

One of the rooms was blocked by a huge canvas with the “Morning of the Streltsy Execution” begun. To capture the whole picture with a glance, Surikov had to look askance at her from a nearby dark room.

In a cramped apartment on Zubovsky Boulevard, hard, tireless, truly titanic work went on for almost three years.

The inspiration that lit up Surikov on Red Square gave him only an inner image, only a general feeling of the future picture. In order to clothe this image in living flesh, it took a long and careful study of historical sources and museum items, it took dozens of preliminary sketches and sketches from nature.

The artist found a description of the execution of archers in the “Diary of a Journey to Muscovy” by Johann Georg Korb, secretary of the Caesar (Austrian) embassy, who was in Russia in 1698-1699.

The source was well chosen. Korb has earned a reputation as a careful and thoughtful observer. The well-known researcher of the Petrine era, historian N. G. Ustryalov, pointed out that Korb wrote with deep respect for Peter, with love for the truth, and if he was mistaken, it was only because he sometimes believed unfounded stories. There are no major inaccuracies in the descriptions of the shootings: Korb described what he saw with his own eyes or knew from direct witnesses. In his detailed and unhurried narration, the atmosphere of the era is sensitively captured.

Executions began in October 1698 in the village of Preobrazhensky and continued into February next year on Red Square in Moscow. Here is how Korb describes the first day of the executions:

“The dwellings of soldiers in Preobrazhenskoye are cut through by the Yauza River flowing there; on the other side of it, on small Moscow carts (which they call cabbies - sbosek), one hundred guilty were planted, awaiting their turn of execution. How many were guilty, as many carts and as many guard soldiers; there were no priests to guide the condemned, as if the criminals were unworthy of this feat of piety; yet everyone held a lit wax candle in their hands so as not to die without light and a cross. The bitter weeping of the wives increased their fear of the impending execution; from everywhere around the crowd of unfortunate groans and cries were heard. The mother wept for her son, the daughter mourned the fate of her father, the unfortunate wife lamented the fate of her husband; in others, the last tears were caused by various ties of blood and properties. And when fast horses carried the condemned to the very place of execution, the women's crying intensified, turning into loud sobs and cries ... From the estate of governor Shein, another one hundred and thirty archers were brought to death. On both sides of all the city gates, two gallows were erected, and each was intended that day for six rebels. When everyone was taken out to the places of execution and each six was distributed to each of the two gallows, his royal majesty in a green Polish caftan arrived, accompanied by many noble Muscovites, to the gate, where, by decree of his royal majesty, the tsar's ambassador stopped in his own carriage with representatives of Poland and Denmark…

Surikov took from this description a number of plot motifs, which later became part of the composition of his painting. He only moved the scene from the village of Preobrazhensky to Moscow. But to understand his plan, it is necessary to give a description of another day of executions that took place already on Red Square.

“This day will be overshadowed by the execution of two hundred people and in any case should be recognized as mournful; all criminals were beheaded. On a very large square, very close to the Kremlin, chopping blocks were placed on which the guilty were supposed to lay down their heads. His royal majesty arrived there in a gig with a certain Alexander, whose company gives him the greatest pleasure, and, having passed the ill-fated square, he entered the place next to it, where thirty condemned men atoned for the crime of their impious intent by death. In the meantime, the disastrous crowd of the guilty filled the space described above, and the king returned there, so that in his presence those who, in his absence, conceived such great wickedness in a blasphemous plan, were punished. The scribe, standing on a bench brought by the soldiers, read the sentence drawn up against the rebels in different places, so that the crowd standing around would know all the better the magnitude of their crime and the correctness of the execution imposed on him. When he fell silent, the executioner began the tragedy: the unfortunates had their own turn, they all approached one after another, not expressing on their faces any grief or horror at the death that threatened them ... One of them was escorted to the block by his wife and children with loud, terrible cries. Preparing to lie down on the chopping block, instead of the last farewell, he gave his wife and little children, who were crying a lot, his mittens and the handkerchief that he had left. Another, who was supposed to kiss the unfortunate chopping block in turn, complained about death, saying that he was forced to undergo it innocently. To this, the king, who was only a step away from him, replied: “Die, unfortunate one! If you turn out to be innocent, then the guilt for your blood will fall on me ”... At the end of the massacre, His Royal Majesty was pleased to dine with General Gordon. The king was by no means in a cheerful mood, but, on the contrary, bitterly complained about the stubbornness and stubbornness of the guilty. He indignantly told General Gordon and the Moscow nobles who were present how one of the convicts showed such inveterateness that, preparing to lie down on the chopping block, he dared to turn to the tsar, who was probably standing very close, with the following words: “Step aside, sir. I should lie down here."

In this passage, Surikov no longer found plot motives for the future picture, but something more important: the moral atmosphere of the executions was described here and the characters of the characters were shown; the pages of the diary of a visiting foreigner clearly reflected both the unshakable courage of the archers and the bitterness of punishing Peter.

Vasily Ivanovich later told how deeply he got used to his theme and how relentless were the thoughts about the bloody days that he decided to depict:

“When I wrote archers, I saw terrible dreams: every night I saw executions in a dream. Smells like blood all around. I was afraid of the night. Wake up and rejoice. Look at the picture. Thank God, there is no such horror in it. All I thought was not to disturb the viewer. To have peace in everything. Everyone was afraid that I would awaken an unpleasant feeling in the viewer. I myself am holy, but others ... I don’t have blood in my picture, and the execution has not yet begun. And I, after all, experienced all this - both blood and executions in myself. ”

In the same years, Repin worked on the painting "Princess Sophia" and, exactly following the instructions of historical sources, depicted a figure, a hanged archer, outside the window of the princess's cell.

In Repin's plan, this figure was necessary: the spectacle of death thickened the tragic atmosphere in which the historical portrait he conceived arose. For Surikov, this turned out to be impossible.

Surikov told Voloshin:

“I remember, “Streltsov” I have almost finished. Ilya Efimovich Repin comes to see and says: “Why don’t you have a single executed person? You would hang here at least on the gallows, on the right plane.

As he left, I wanted to try. I knew that it was impossible, but I wanted to know what would have happened. I drew with chalk the figure of a hanged archer. And just then the nanny entered the room, - as she saw it, she collapsed without feelings.

Even that day, Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov stopped by: “What are you, want to spoil the whole picture?” - Yes, so that I, I say, sold my soul like that! Is that possible?”

Surikov refused to depict the execution, not only because he was repulsed by the rough physiology of the suffering and the streams of blood shed on Red Square (“Everyone was afraid that I would awaken an unpleasant feeling in the viewer”). The artist also had deeper foundations.

The dramatic effect created by the spectacle of torment and death, perhaps, would shock the audience, but at the same time it would inevitably reduce the plot of the picture to a private episode from the history of the archery revolt. And the artist wanted to concentrate in a single moment the very essence of the historical event he had chosen - to show a national tragedy. Depicting not execution, but only its expectation, Surikov could show the streltsy mass and Peter himself in all the fullness of their spiritual and physical strength, to reveal to the viewer the high spiritual beauty of the Russian people.

"Morning of Streltsy executions": someone called them well. I wanted to convey the solemnity of the last minutes, but not the execution at all, ”the artist later said.

Having deeply experienced his theme, mentally becoming, as it were, a participant in the historical drama, Surikov organized the material gleaned from historical sources in his own way.

In the picture, separate motifs are merged into a single whole, selected from different places in Korb's diary, and all of them are subject to one general spiritual mood - the solemnity of the last minutes.

It was a real creative rearrangement of the material. The feeling invested by the artist in the picture filled the historical images with the breath of true life.

“In a historical picture, after all, it is not necessary that it be completely so, but that there be a possibility, that it should be similar. The point is historical picture- guessing. If only the spirit of the time itself is observed, you can make any mistakes in the details. And when everything is point to point, it’s even disgusting, ”Surikov himself said.

The action in the film "Morning of the Streltsy Execution" takes place on Red Square, against the backdrop of the Kremlin towers and St. Basil's Cathedral. When looking at the picture, it seems that it is filled with an innumerable crowd. The people are worried, “like the sound of many waters,” as the artist liked to say. But all the boundless variety of poses, clothes, characters is brought to an amazing wholeness, to an indissoluble and harmonious unity. The Surikov crowd lives a common life, all its constituent parts are interconnected, as in a living organism, and at the same time, each face is individual, each character is unique and deeply thought out.

Already in a pencil sketch made by the artist on the back of a sheet of sheet music for the guitar, the peculiarity of the conceived picture clearly stands out: it does not have a separate “hero” in whose image the meaning of the work would be embodied. There is Peter in the picture, there are characteristic types of archers that carry a particularly large semantic load, but they are not singled out from the crowd, they are not opposed to it. The content of "The Morning of the Archery Execution" is revealed only in the action of the masses. The hero of the picture becomes the people themselves, and its theme is the people's tragedy.

The understanding of history as a movement of the masses was the big new word that marked the work of Surikov in historical painting. Mass historical scenes were painted by Bryullov, the image of the crowd played a major role in the concept of Ivanov's "The Appearance of Christ to the People", but only Surikov brought to the end the thoughts of his great predecessors.

Surikov considered the national character to be the key to the correct interpretation of the historical life of the people. To reveal this character, to help the viewer look into the spiritual world of ordinary Russian people - the artist saw a similar goal in front of him while working on "The Morning of the Streltsy Execution".

Hence comes the inexhaustible variety of folk types in the picture and at the same time their inner relationship. They are all similar and not similar to each other.

Sagittarius are imbued with the "solemnity of the last minutes", the spiritual strength of the archers is not broken, they all face death without fear. But a single feeling is refracted in them in different ways.

A red-haired archer in a red cap, convulsively squeezing a burning candle, raises his gaze, full of indomitable hatred, and, as it were, throws down a silent challenge to the winner. He could have said to Peter: “Step aside, sir. I should lie down here!” Another, a tall, elderly black-bearded archer, in a red caftan thrown over his shoulders, does not seem to notice his surroundings at all: he is so deeply immersed in his last thoughts. Further, almost in the very center of the picture, a gray-haired old man in a white shirt, majestically calm, courageously waiting for death, finds the strength in himself to console his crying children. Next to him, one of the archers, bent, apparently weakened from torture, stood on the cart and gives the people his last bow; he turned his back on the king and asks for forgiveness not from Peter, but from the people.

The harsh firmness and courage of the archers is opposed by the unbridled grief of the archers' children and wives. It seems that Surikov has exhausted the whole gamut of feelings here, from a violent explosion of despair to silent hopeless grief: unchildish fear distorts the face of a tiny girl lost in the crowd; the archer, separated from her husband, sobs uncontrollably; in mute despair, a decrepit old woman sank to the ground, seeing off her son ...

The figures of the Preobrazhensky soldiers, the executors of Peter's will, mingle with the streltsy crowd. In characterizing these, essentially secondary, characters, Surikov showed special psychological insight.

The soldiers are spiritually close to the archers, they are representatives of the simple Russian people. But at the same time, they seem to represent new Russia, which replaced pre-Petrine Russia. Without hesitation, they lead the condemned archers to execution, but there is nothing hostile in their treatment of the rebels. The young Preobrazhensky, standing near the black-bearded archer, looks at him with an expression of hidden pity. The soldier leading the archer to the gallows put his arm around him and supports him almost like a brother. Surikov acutely felt and truthfully expressed the complex, ambivalent attitude of the soldiers to the ongoing execution.

On the right side of the picture is Peter with his retinue.

In the royal retinue, no one is endowed with the expressiveness and strength of character that marks the images of archers - the interest and sympathy of the artist is not here.

In the foreground, like an indifferent witness, a gray-bearded boyar in a red coat looks indifferently in front of him. Behind him is a group of foreigners, in one of them, intensely and thoughtfully peering into the crowd, critics guess an imaginary portrait of Korb, the author of Journey to Muscovy. Further - some women look out of the windows of the carriage. But next to these secondary characters, the figure of Peter is sharply highlighted.

Peter's face with his angry and resolute look expresses unshakable confidence, in his whole figure, tense and impetuous, one feels a huge inner strength. Just like his opponents, Peter passionately believes in his rightness and, punishing the rebellious archers, sees them not as personal enemies, but as enemies of the state, destroyers of the Russian future.

He alone opposes the entire streltsy crowd, and his image becomes as ideologically significant as the collective image of the masses. In Surikov's interpretation, Peter is also the representative of the people and the bearer of the national character, like the archers.

This is where the meaning of the folk tragedy embodied in the “Morning of the Streltsy Execution” is revealed: the Russians are fighting the Russians, and each side has a deep consciousness of the rightness of its cause. Streltsy respond with rebellion to the oppression of the people, Peter defends the future of Russia, which he himself led to new paths.

Korb's notes gave Surikov only a starting point for the realization of his plan. The main source of Surikov's images was living reality itself.

“When I conceived them,” Surikov told Voloshin, “all my faces appeared at once. And coloring along with the composition. After all, I live from the canvas itself: everything arises from it. Remember, there I have an archer with a black beard - this is ... Stepan Fedorovich Torgoshin, my mother's brother. And the women - you know, I and my relatives had such old women. Sarafannitsy, though Cossacks. And the old man in "Sagittarius" is an exiled one, about seventy years old. I remember walking, carrying a bag, swaying from weakness - and bowing to the people.

Genuine historicism, deeply characteristic of Surikov, appears nowhere so clearly as precisely in this ability to see the past in the present, the historical image in living modern reality. Surikov does not modernize the past, transferring the features of the present into it, but through careful and accurate selection he reveals the most typical and, therefore, the most viable and persistent signs of the national character that lived and manifested themselves in the distant past, live and manifest themselves today.

The image found by the artist was sometimes subjected to several successive stages of processing, and everything accidental and insignificant fell away and the main, defining features of the character were persistently emphasized.

Sketches have been preserved in which Surikov looked for a type of red-bearded archer.

Repin tells about the beginning of the search: “Amazed by the similarity of the one archer he had outlined, sitting in a cart with a lit candle in his hand, I persuaded Surikov to go with me to the Vagankovskoye cemetery, where one gravedigger was a miracle type. Surikov was not disappointed: Kuzma posed for him for a long time, and Surikov, with the name of Kuzma, even later lit up with feeling from his gray eyes, kite-like nose and reclined forehead.

Surikov himself also mentioned this to Kuzma: “The red-haired archer is a gravedigger, I saw him in the cemetery. I tell him: "Let's go to me - pose." He was about to put his foot into the sledge, and his comrades began to laugh. He says, "I don't want to." And by nature, after all, such as a Sagittarius. The deep-set eyes startled me. Evil, rebellious type. The name was Kuzma. Chance: the catcher and the beast runs. Forcefully persuaded him. He, as he posed, asked: “What, will they chop my head off, or what?” And a sense of delicacy stopped me from telling those from whom I wrote that I was writing an execution.

In the first sketches made by Surikov from Kuzma, his features still bear little resemblance to the appearance of an implacable and passionate rebel, whom we see in the picture. Before us is a characteristic, strong-willed, but calm face, striking only by its resemblance to the profile, briefly drawn in the first compositional sketch of “Morning of the Streltsy Execution”, that is, even before Surikov’s meeting with the gravedigger Kuzma. In subsequent sketches, the artist, as it were, evokes on the face of his model those feelings that once animated the rebellious archer. The lines of the silhouette become sharper, wrinkles deepen, the expression becomes more tense, a furious gleam lights up in sunken eyes - and through the features of the gravedigger, the image of an indomitable and passionate Moscow rebel comes through more and more clearly.

Other persons who served Surikov in kind were also reworked. In the portrait study of the black-bearded archer - Stepan Fedorovich Torgoshin - the features of everyday life have not yet been overcome. Only in the picture he is transformed and poeticized.

The "Study of a Seated Old Woman" still bears traces of direct copying of the model, and the image of the old archer in the picture, in terms of the power of generalization and poetry, echoes the images of the folk epic.

The deep ideological content of "The Morning of the Streltsy Execution" led to a holistic and perfect artistic form.

Surikov said that the idea of a painting is born in his mind along with the form, and the thought is inseparable from the pictorial image. When he conceived The Morning of the Streltsy Execution, in front of him, in his words, “all the faces appeared at once. And coloring along with composition. But just as it happened when solving an ideological concept, the initial inspiration gave the artist only the general outlines of the task that was to be carried out on canvas.

“The main thing for me is composition,” said Surikov. “There is some kind of firm, inexorable law that can only be guessed by intuition, but which is so immutable that each added or subtracted inch of the canvas or an extra set point changes the entire composition at once.”

Surikov achieved unity and rhythmic completeness of the whole, never compromising the naturalness and expressiveness of the grouping of figures and the structure of the form. His composition is based not on dead schemes worked out once and for all, but on direct, keen observation of nature. No wonder he studied so carefully "how people grouped in the street." In life itself, he revealed the laws of harmonious and integral construction.

The scene of action in the picture is closed by the image of the Kremlin walls and St. Basil's Cathedral.

Already in the first pencil sketch of the future composition, the silhouette of the cathedral is outlined. A mute witness to the past, a remarkable monument of ancient Russian architecture, so closely connected in Surikov's mind with the "Morning of the Streltsy Execution", significantly influenced the artistic decision of the picture.

In the composition "Morning of the Archery Execution" there are hidden correspondences with the architecture of St. Basil the Blessed. The crowd in the picture is united by the same broad measured rhythms that connect the pillars and domes of the ancient Russian temple. characteristic feature the cathedral is a kind of asymmetry and a bizarre combination of various architectural and ornamental forms, brought, however, to a stable and harmonious unity. Surikov aptly captured this unity in diversity and recreated it in the image of the streltsy crowd.

Even more obvious is the influence of St. Basil's Cathedral on the color system of the "Morning of the Streltsy Execution". In the coloring of the cathedral with its green-blue, white and rich red tones, the color key of the whole picture is given, as it were. The same tones, only in a more intense sound, pass through the entire composition.

Surikov strove for realistic naturalness and harmony of color. The combination of colors in his painting truly conveys the feeling of a gloomy, damp October morning; in motionless autumn air all shades and color transitions are especially clearly distinguished. Color in Surikov becomes the bearer of the characteristic of feeling. The artist himself pointed out that a significant role in the color scheme was played by the effect he once noticed of combining daylight with a burning candle, throwing reflexes onto a white canvas. Lighted candles in the hands of archers dressed in white shirts, according to Surikov's plan, were supposed to create that special, disturbing feeling that marked the solemnity of the last minutes. This feeling is enhanced by the contrast of white with rich red, passing through the whole picture.

“And the arcs are carts for the Streltsy,” I wrote about the markets. You write and think - this is the most important thing in the whole picture, ”said Surikov.

These words should not be taken literally: “the most important” for Surikov was not decorative details. But he acutely felt and - the first among Russian artists - revealed in his picture the organic, inextricable connection of the Russian character with national folk art. So, the silhouette of an archer bowed in a farewell bow resembles; as noted by the Soviet art critic A. M. Kuznetsov, an ancient Russian icon from the “rank”. Depicting the ornaments of St. Basil the Blessed, painted arches, embroidered caftans and patterned dresses of women, Surikov introduced the whole world of Russian beauty, which has developed in folk art, into the Morning of the Streltsy.

On the day of the assassination of the tsar, March 1, 1881, the IX traveling exhibition opened, where for the first time the “Morning of the Streltsy Execution” appeared before the audience - a picture whose hero was the people.

Repin wrote to Surikov: “Vasily Ivanovich! The picture makes a big impression on almost everyone. The drawing is criticized, and especially Kuzya is attacked, the lousy academic party is the most ardent of all: they say that on Sunday Zhuravlev grimaced indecently, I did not see it. Chistyakov praises. Yes, all decent people are touched by the picture. It was written in Novoye Vremya on March 1st, in the Order on March 1st. Well, then an event happened, after which there is no time for pictures yet ... "

The intrigues of the “academic party” also found a response in the press. A review appeared in one of the reactionary newspapers, which placed "The Morning of the Streltsy "Execution"" below any mediocrity. But in general, criticism reacted to Surikov rather sympathetically. The picture was praised - however, with many reservations. “... The deep plan is not entirely fulfilled due to the weak perspective that is too heaped up with figures, but the details of the picture are of great merit,” wrote, for example, Russkiye Vedomosti.

What happened next was almost always repeated with Surikov's paintings: in the condescendingly restrained praise of criticism, a complete misunderstanding of the artist's originality was seen through. Innovation and deep ideological Surikov were not up to modern criticism.

Even the ardent fighter for national Russian art, the critic V. V. Stasov, who usually noted with great sensitivity everything original and talented in contemporary art, this time preferred to refrain from reviewing The Morning of the Streltsy Execution. Repin wrote to him shortly after the opening of the exhibition: “I still cannot understand one thing, how is it that Surikov’s painting “The Execution of Streltsy” did not inflame you?” And in the next letter, he again returns to the same thing: “Most of all, I am angry with you for letting Surikov pass. How did it happen? After compliments even Makovskaya (this is worthy of a gallant gentleman) suddenly pass in silence of such an elephant !!! I don’t understand - it terribly blew me up. ”

Surikov received unconditional recognition only from the leading Wanderers.

Repin, who closely followed Surikov's work on The Morning of the Archery Execution and was the first to highly appreciate this picture, wrote to P. M. Tretyakov:

“Surikov's painting makes an irresistible, deep impression on everyone. All with one voice expressed their readiness to give her the best place; everyone has written on their faces that she is our pride at this exhibition ... A powerful picture! Well, yes, they will write to you about it ... It was decided to offer Surikov immediately member our partnership." Only a few have received this honor.

"Morning of the Streltsy Execution" at the same time became part of the wonderful gallery of Russian art, created by a Moscow collector and public figure Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov.

From the first picture of Surikov, threads stretch to his further plans. "Streltsy" together with "Menshikov in Berezov" and "Boyarina Morozova" constitute a closed cycle devoted, in essence, to one circle of problems.

The folk tragedy that became the theme of "The Morning of the Archery Execution" had a prologue that took place in the second half of the 17th century, at the time when Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, together with Patriarch Nikon, reformed the Russian Church. A split movement rose up against the reform.

In 1881, Surikov made the first compositional sketches of the painting Boyar Morozova.

Following the era of Peter's reforms, the time came for reaction and foreign dominance, the time for the fall of Peter's followers.

Surikov made the tragedy of one of the largest figures of the time of Peter the Great the subject of his second big picture.

He turned to work on "Menshikov in Berezov" immediately after the "Morning of the Streltsy Execution".

Group of artists-peredvizhniki. 1899.

In Surikov. Detail of the painting "Menshikov in Berezov" (the eldest daughter of Meishikov) (PT).

From the book Applause author Gurchenko Ludmila MarkovnaExecutions On each house the Germans hung out orders-announcements. They said that at such and such a time, all healthy and sick people, with children, regardless of age, should gather there. For failure to comply with the order - execution. The main place of all events in the city was our Blagoveshchensky

From the book My Adult Childhood author Gurchenko Ludmila MarkovnaEXECUTIONS On each house the Germans hung out orders-announcements. They said that at such and such a time, all healthy and sick people, with children - regardless of age - should gather there. For failure to comply with the order - execution. The main place of all events in the city was our Blagoveshchensky

Vilchur Jacek

1943 - On the eve of the execution on January 3, he was at the investigation three times. Every time it started the same way and ended the same way. During the interrogation, the interpreter beat me on the hands. On January 4, they put me in a car and took me to the bycircus on Kazimirovskaya. Little has changed here

From the book After the Execution author Boyko Vadim YakovlevichA Word After the Execution 79-year-old Kiev resident Vadim Boyko is the only person who managed to escape from the gas chamber a few seconds before the armored doors slammed shut and the Zyklon B gas was released. He managed to survive after being shot on June 28, 1943 in

From the book Reflections of a Wanderer (collection) author Ovchinnikov Vsevolod VladimirovichTwenty years after the execution In the summer of 1964, Viktor Mayevsky, a political observer for Pravda, flew to Japan. He said that at the dacha at Khrushchev's they showed the French detective "Who are you, Dr. Sorge." After the film, Nikita Sergeevich rhetorically uttered: “Is it reasonable

From the book With Your Eyes author Adelheim Pavel3. Method of execution Anyone who thinks that Marxists repeat the liberal slogans of the French Republic or Western democracy about freedom of conscience will not understand the position of religion in the Soviet state. In the Marxist sense, "freedom" has the opposite meaning. Democrats say

From Garibaldi's book author Lurie Abram YakovlevichSENTENCED TO DEATH After returning from a voyage, Garibaldi in the same 1833 found Mazzini in Marseilles and through a certain Covey met him. It was a meeting of two outstanding people. Bronze sailor with a manly face, framed by falling on his shoulders

From the book of Surikov author Gor Gennady SamoilovichV. “MORNING OF THE STRELETSKY EXECUTION” The event depicted by Surikov in his first large painting, “The Morning of the Streltsy Execution,” marked a turning point in modern Russian history.

From the book The main enemy. Secret war for the USSR author Dolgopolov Nikolai MikhailovichOn Fridays, I was taken to executions by Aleksey Mikhailovich Kozlov, one of the few people belonging to the small world intelligence clan who are destined to live several lives at once. At the same time, each is full of dangers and incredible events, and for the most part

From the book Tenderer than the sky. Collection of poems author Minaev Nikolai NikolaevichSpring morning (“The morning is quiet and clear ...”) The morning is quiet and clear Today pleases my eyes; The red sun emerges from behind the forest into space. Grass and sleepy maple shine with silvery moisture, And fragrant bird cherry The fresh air is filled with drink. The sky is clear, serene, not a cloud

From the book of the Head of the Russian State. Outstanding rulers that the whole country should know about author Lubchenkov Yury NikolaevichPeter's executions Before me, the chopping block Stands up in the square, The red shirt Does not let me forget. In the meadow to praise the will With a scythe goes a mower. The Tsar of Moscow is coming to bloody Moscow. Archers, put out the candles! To you, mowers, thieves, The last shame is breaking. Wow, bums

From the book of Reminiscences (1915–1917). Volume 3 author Dzhunkovsky Vladimir FyodorovichRestoration of the death penalty for treason On July 14, an order was issued by the Military Department with a decree of the Provisional Government, which finally decided to take emergency measures to keep the army from final collapse No. 441.

The painting by Jacques Louis David "The Oath of the Horatii" is a turning point in the history of European painting. Stylistically, it still belongs to classicism; it is a style oriented towards Antiquity, and at first glance this orientation is retained by David. The Oath of the Horatii is based on the story of how the Roman patriots, the three brothers Horace, were chosen to fight against the representatives of the hostile city of Alba Longa, the brothers Curiatii. Titus Livius and Diodorus Siculus have this story; Pierre Corneille wrote a tragedy on its plot.

“But it is precisely the oath of the Horatii that is missing from these classical texts.<...>It is David who turns the oath into the central episode of the tragedy. The old man is holding three swords. He stands in the center, he represents the axis of the picture. To his left are three sons merging into one figure, to his right are three women. This picture is amazingly simple. Before David, classicism, for all its orientation towards Raphael and Greece, could not find such a harsh, simple masculine language for expressing civic values. David seemed to hear what Diderot was saying, who did not have time to see this canvas: “You must write as they said in Sparta.”

Ilya Doronchenkov

In the time of David, Antiquity first became tangible through the archaeological discovery of Pompeii. Before him, Antiquity was the sum of the texts of ancient authors - Homer, Virgil and others - and a few dozen or hundreds of imperfectly preserved sculptures. Now it has become tangible, down to furniture and beads.

“But none of that is in David's picture. In it, Antiquity is strikingly reduced not so much to the surroundings (helmets, irregular swords, togas, columns), but to the spirit of primitive furious simplicity.

Ilya Doronchenkov

David carefully staged the appearance of his masterpiece. He painted and exhibited it in Rome, garnering enthusiastic criticism there, and then sent a letter to a French patron. In it, the artist reported that at some point he stopped painting for the king and began to paint it for himself, and, in particular, decided to make it not square, as required for the Paris Salon, but rectangular. As the artist expected, the rumors and the letter fueled public excitement, the painting was booked into an advantageous place at the already opened Salon.

“And so, belatedly, the picture is put into place and stands out as the only one. If it were square, it would be hung in a row of others. And by changing the size, David turned it into a unique one. It was a very powerful artistic gesture. On the one hand, he declared himself as the main one in creating the canvas. On the other hand, he riveted everyone's attention to this picture.

Ilya Doronchenkov

The picture has another important meaning, which makes it a masterpiece for all time:

“This canvas does not appeal to the individual - it refers to the person standing in the ranks. This is a team. And this is a command to a person who first acts and then thinks. David very correctly showed two non-intersecting, absolutely tragically separated worlds - the world of acting men and the world of suffering women. And this juxtaposition - very energetic and beautiful - shows the horror that actually stands behind the story of the Horatii and behind this picture. And since this horror is universal, then the "Oath of the Horatii" will not leave us anywhere.

Ilya Doronchenkov

Abstract

In 1816, the French frigate Medusa was wrecked off the coast of Senegal. 140 passengers left the brig on a raft, but only 15 escaped; they had to resort to cannibalism in order to survive the 12-day wandering on the waves. A scandal erupted in French society; the incompetent captain, a royalist by conviction, was found guilty of the disaster.

“For liberal French society, the catastrophe of the frigate Medusa, the sinking of the ship, which for a Christian person symbolizes the community (first the church, and now the nation), has become a symbol, a very bad sign of the beginning of a new Restoration regime.”

Ilya Doronchenkov

In 1818, the young artist Théodore Géricault, looking for a worthy subject, read the book of the survivors and set to work on his painting. In 1819, the painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon and became a hit, a symbol of romanticism in painting. Géricault quickly abandoned his intention to portray the most seductive scene of cannibalism; he did not show stabbing, despair, or the very moment of salvation.

“Gradually, he chose the only right moment. This is the moment of maximum hope and maximum uncertainty. This is the moment when the people who survived on the raft first see the Argus brig on the horizon, which first passed the raft (he did not notice it).

And only then, going on a collision course, stumbled upon him. On the sketch, where the idea has already been found, Argus is noticeable, but in the picture it turns into a small dot on the horizon, disappearing, which attracts the eye, but, as it were, does not exist.Ilya Doronchenkov

Gericault renounces naturalism: instead of emaciated bodies, he has beautiful courageous athletes in his picture. But this is not idealization, this is universalization: the picture is not about specific Meduza passengers, it is about everyone.

“Géricault scatters the dead in the foreground. He did not invent it: the French youth raved about the dead and wounded bodies. It excited, hit on the nerves, destroyed conventions: a classicist cannot show the ugly and terrible, but we will. But these corpses have another meaning. Look at what is happening in the middle of the picture: there is a storm, there is a funnel into which the eye is drawn. And over the bodies, the viewer, standing right in front of the picture, steps onto this raft. We are all there."

Ilya Doronchenkov

Géricault's painting works in a new way: it is addressed not to an army of spectators, but to every person, everyone is invited to the raft. And the ocean is not just an ocean of lost hopes in 1816. This is the destiny of man.

Abstract

By 1814, France was tired of Napoleon, and the arrival of the Bourbons was received with relief. However, many political freedoms were abolished, the Restoration began, and by the end of the 1820s, the younger generation began to realize the ontological mediocrity of power.

“Eugène Delacroix belonged to that stratum of the French elite that rose under Napoleon and was pushed aside by the Bourbons. Nevertheless, he was favored: he received a gold medal for his first painting at the Salon, Dante's Boat, in 1822. And in 1824, he made the painting “Massacre on Chios”, depicting ethnic cleansing, when the Greek population of the island of Chios was deported and destroyed during the Greek War of Independence. This is the first sign of political liberalism in painting, which touched still very distant countries.

Ilya Doronchenkov

In July 1830, Charles X passed several laws severely restricting political freedoms and sent troops to sack the printing press of an opposition newspaper. But the Parisians responded by shooting, the city was covered with barricades, and during the "Three Glorious Days" the Bourbon regime fell.

The famous painting by Delacroix, dedicated to the revolutionary events of 1830, shows different social strata: a dandy in a top hat, a tramp boy, a worker in a shirt. But the main one, of course, is a beautiful young woman with bare breasts and a shoulder.

“Delacroix succeeds here with something that almost never happens with artists of the 19th century, who are thinking more and more realistically. He manages in one picture - very pathetic, very romantic, very sonorous - to combine reality, physically tangible and brutal (look at the corpses in the foreground beloved by romantics) and symbols. Because this full-blooded woman is, of course, Freedom itself. Political development since the 18th century has made it necessary for artists to visualize what cannot be seen. How can you see freedom? Christian values are conveyed to a person through something very human - through the life of Christ and his suffering. And such political abstractions as freedom, equality, fraternity have no shape. And now Delacroix, perhaps the first and, as it were, not the only one who, in general, successfully coped with this task: we now know what freedom looks like.

Ilya Doronchenkov

One of the political symbols in the painting is the Phrygian cap on the girl's head, a permanent heraldic symbol of democracy. Another talking motif is nakedness.

“Nudity has long been associated with naturalness and nature, and in the 18th century this association was forced. The history of the French Revolution even knows a unique performance, when a naked French theater actress portrayed nature in Notre Dame Cathedral. And nature is freedom, it is naturalness. And that's what, it turns out, this tangible, sensual, attractive woman means. It signifies natural liberty."

Ilya Doronchenkov

Although this painting made Delacroix famous, it was soon removed from view for a long time, and it is clear why. The spectator standing in front of her finds herself in the position of those who are attacked by Freedom, who are attacked by the revolution. It is very uncomfortable to look at the unstoppable movement that will crush you.

Abstract

On May 2, 1808, an anti-Napoleonic rebellion broke out in Madrid, the city fell into the hands of the protesters, but by the evening of the 3rd, mass executions of rebels were taking place in the vicinity of the Spanish capital. These events soon led to guerrilla war, which lasted six years. When it is over, two paintings will be commissioned from the painter Francisco Goya to commemorate the uprising. The first is "The uprising of May 2, 1808 in Madrid."

“Goya really depicts the moment the attack began - that first Navajo strike that started the war. It is this compactness of the moment that is extremely important here. He seems to bring the camera closer, from the panorama he moves to exclusively close plan, which also did not exist to such an extent before him. There is another exciting thing: the feeling of chaos and stabbing is extremely important here. There is no person here that you feel sorry for. There are victims and there are killers. And these murderers with bloodshot eyes, Spanish patriots, in general, are engaged in butchering.

Ilya Doronchenkov

In the second picture, the characters change places: those who are cut in the first picture, in the second picture, those who cut them are shot. And the moral ambivalence of the street fight is replaced by moral clarity: Goya is on the side of those who rebelled and die.

“The enemies are now divorced. On the right are those who will live. It's a series of people in uniform with guns, exactly the same, even more the same than David's Horace brothers. Their faces are invisible, and their shakos make them look like machines, like robots. These are not human figures. They stand out in a black silhouette in the darkness of the night against the backdrop of a lantern flooding a small clearing.

On the left are those who die. They move, swirl, gesticulate, and for some reason it seems that they are taller than their executioners. Although the main, central character - a Madrid man in orange pants and a white shirt - is on his knees. He is still taller, he is a little on a hillock.

Ilya Doronchenkov

The dying rebel stands in the pose of Christ, and for greater persuasiveness, Goya depicts stigmata on his palms. In addition, the artist makes you go through a difficult experience all the time - look at the last moment before the execution. Finally, Goya changes the understanding of the historical event. Before him, an event was portrayed by its ritual, rhetorical side; in Goya, an event is an instant, a passion, a non-literary cry.

In the first picture of the diptych, it can be seen that the Spaniards are not slaughtering the French: the riders falling under the horse's feet are dressed in Muslim costumes.

The fact is that in the troops of Napoleon there was a detachment of Mamelukes, Egyptian cavalrymen.

“It would seem strange that the artist turns Muslim fighters into a symbol of the French occupation. But this allows Goya to turn a contemporary event into a link in the history of Spain. For any nation that forged its self-consciousness during Napoleonic Wars, it was extremely important to realize that this war is part of the eternal war for their values. And such a mythological war for the Spanish people was the Reconquista, the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslim kingdoms. Thus, Goya, while remaining faithful to documentary, modernity, puts this event in connection with the national myth, forcing us to realize the struggle of 1808 as the eternal struggle of the Spaniards for the national and Christian.

Ilya Doronchenkov

The artist managed to create an iconographic formula of execution. Every time his colleagues - be it Manet, Dix or Picasso - turned to the topic of execution, they followed Goya.

Abstract

The pictorial revolution of the 19th century, even more tangibly than in the event picture, took place in the landscape.

“The landscape completely changes the optics. Man changes his scale, man experiences himself in a different way in the world. A landscape is a realistic depiction of what is around us, with a sense of moisture-laden air and everyday details in which we are immersed. Or it can be a projection of our experiences, and then in the play of sunset or in a joyful sunny day we see the state of our soul. But there are striking landscapes that belong to both modes. And it's very hard to know, really, which one is dominant."

Ilya Doronchenkov

This duality is clearly manifested by the German artist Caspar David Friedrich: his landscapes both tell us about the nature of the Baltic, and at the same time represent a philosophical statement. There is a lingering sense of melancholy in Friedrich's landscapes; a person rarely penetrates them beyond the background and usually turns his back to the viewer.

In his last painting, Ages of Life, a family is depicted in the foreground: children, parents, an old man. And further, behind the spatial gap - the sunset sky, the sea and sailboats.

“If we look at how this canvas is built, we will see a striking echo between the rhythm of human figures in the foreground and the rhythm of sailboats in the sea. Here are tall figures, here are low figures, here are big sailboats, here are boats under sail. Nature and sailboats - this is what is called the music of the spheres, it is eternal and does not depend on man. The man in the foreground is his finite being. The sea in Friedrich is very often a metaphor for otherness, death. But death for him, a believer, is a promise of eternal life, about which we do not know. These people in the foreground - small, clumsy, not very attractively written - follow the rhythm of a sailboat with their rhythm, as a pianist repeats the music of the spheres. This is our human music, but it all rhymes with the very music that for Friedrich fills nature. Therefore, it seems to me that in this canvas Friedrich promises - not an afterlife paradise, but that our finite being is still in harmony with the universe.

Ilya Doronchenkov

Abstract

After the French Revolution, people realized that they had a past. The 19th century, through the efforts of romantic aesthetes and positivist historians, created the modern idea of history.

“The 19th century created history painting as we know it. Non-distracted Greek and Roman heroes, acting in an ideal environment, guided by ideal motives. The history of the 19th century becomes theatrical and melodramatic, it approaches man, and we are now able to empathize not with great deeds, but with misfortunes and tragedies. Each European nation created its own history in the 19th century, and constructing history, it, in general, created its own portrait and plans for the future. In this sense, European historical painting of the 19th century is terribly interesting to study, although, in my opinion, it did not leave, almost did not leave truly great works. And among these great works, I see one exception, which we Russians can rightly be proud of. This is Vasily Surikov's "Morning of the Streltsy Execution".

Ilya Doronchenkov

19th-century history painting, oriented towards external plausibility, usually tells of a single hero who directs history or fails. Surikov's painting here is a striking exception. Her hero is a crowd in colorful outfits, which takes up almost four-fifths of the picture; because of this, the picture seems to be strikingly disorganized. Behind the live swirling crowd, part of which will soon die, stands the colorful, agitated St. Basil's Cathedral. Behind the frozen Peter, a line of soldiers, a line of gallows - a line of battlements of the Kremlin wall. The picture is held together by the duel of the views of Peter and the red-bearded archer.

“A lot can be said about the conflict between society and the state, the people and the empire. But it seems to me that this thing has some more meanings that make it unique. Vladimir Stasov, a propagandist of the work of the Wanderers and a defender of Russian realism, who wrote a lot of superfluous things about them, spoke very well about Surikov. He called paintings of this kind "choral". Indeed, they lack one hero - they lack one engine. The people are the driving force. But in this picture the role of the people is very clearly visible. Joseph Brodsky in his Nobel lecture perfectly said that the real tragedy is not when the hero dies, but when the choir dies.

Ilya Doronchenkov

Events take place in Surikov's paintings as if against the will of their characters - and in this the concept of the artist's history is obviously close to Tolstoy's.

“Society, people, nation in this picture seem to be divided. Soldiers of Peter in a uniform that seems black, and archers in white are contrasted as good and evil. What connects these two unequal parts of the composition? This is an archer in a white shirt, going to execution, and a soldier in uniform, who supports him by the shoulder. If we mentally remove everything that surrounds them, we will never be able to assume that this person is being led to execution. They are two buddies who are returning home, and one supports the other in a friendly and warm manner. When Petrusha Grinev was hanged by the Pugachevites in The Captain's Daughter, they said: “Don't knock, don't knock,” as if they really wanted to cheer him up. This feeling that a people divided by the will of history is at the same time fraternal and united is the amazing quality of Surikov’s canvas, which I also don’t know anywhere else.”

Ilya Doronchenkov

Abstract

In painting, size matters, but not every subject can be depicted on a large canvas. Different pictorial traditions depicted the villagers, but most often not in huge paintings, but this is precisely the “Funeral at Ornans” by Gustave Courbet. Ornan is a prosperous provincial town, where the artist himself comes from.

“Courbet moved to Paris but did not become part of the artistic establishment. He did not receive an academic education, but he had powerful hand, a very tenacious look and great ambition. He always felt like a provincial, and he was best at home, in Ornan. But he lived almost all his life in Paris, fighting with the art that was already dying, fighting with the art that idealizes and talks about the general, about the past, about the beautiful, not noticing the present. Such art, which rather praises, which rather delights, as a rule, finds a very large demand. Courbet was, indeed, a revolutionary in painting, although now this revolutionary nature of him is not very clear to us, because he writes life, he writes prose. The main thing that was revolutionary in him was that he stopped idealizing his nature and began to write it exactly as he sees, or as he believed that he sees.

Ilya Doronchenkov

About fifty people are depicted in a giant picture almost in full growth. All of them are real persons, and experts have identified almost all the participants in the funeral. Courbet painted his countrymen, and they were pleased to get into the picture exactly as they are.

“But when this painting was exhibited in 1851 in Paris, it created a scandal. She went against everything that the Parisian public was used to at that moment. She offended the artists with the lack of a clear composition and rough, dense impasto painting, which conveys the materiality of things, but does not want to be beautiful. She frightened off the ordinary person by the fact that he could not really understand who it was. Striking was the disintegration of communications between the audience of provincial France and the Parisians. The Parisians took the image of this respectable wealthy crowd as the image of the poor. One of the critics said: “Yes, this is a disgrace, but this is the disgrace of the province, and Paris has its own disgrace.” Under the ugliness, in fact, was understood the ultimate truthfulness.

Ilya Doronchenkov

Courbet refused to idealize, which made him a true avant-garde artist of the 19th century. He focuses on French popular prints, and on a Dutch group portrait, and on antique solemnity. Courbet teaches us to perceive modernity in its originality, in its tragedy and in its beauty.

“French salons knew images of hard peasant labor, poor peasants. But the image mode was generally accepted. The peasants needed to be pitied, the peasants needed to be sympathized with. It was a view from above. A person who sympathizes is, by definition, in a priority position. And Courbet deprived his spectator of the possibility of such patronizing empathy. His characters are majestic, monumental, they ignore their viewers, and they do not allow you to establish such a contact with them that makes them part of the familiar world, they break stereotypes very powerfully.

Ilya Doronchenkov

Abstract

The 19th century did not like itself, preferring to look for beauty in something else, be it Antiquity, the Middle Ages or the East. Charles Baudelaire was the first to learn to see the beauty of modernity, and it was embodied in painting by artists whom Baudelaire was not destined to see: for example, Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet.

“Manet is a provocateur. Manet is at the same time a brilliant painter, whose charm of colors, colors that are very paradoxically combined, makes the viewer not ask himself obvious questions. If we look closely at his paintings, we will often be forced to admit that we do not understand what brought these people here, what they are doing next to each other, why these objects are connected on the table. The simplest answer is: Manet is primarily a painter, Manet is primarily an eye. He is interested in the combination of colors and textures, and the logical conjugation of objects and people is the tenth thing. Such pictures often confuse the viewer who is looking for content, who is looking for stories. Mane does not tell stories. He could have remained such an amazingly accurate and refined optical apparatus if he had not created his latest masterpiece already in those years when he was possessed by a fatal disease.

Ilya Doronchenkov

The painting "The Bar at the Folies Bergère" was exhibited in 1882, at first earned ridicule from critics, and then was quickly recognized as a masterpiece. Its theme is the cafe-concert, a striking phenomenon of Parisian life in the second half of the century. It seems that Manet vividly and reliably captured the life of the Folies Bergère.

“But when we start to look closely at what Manet did in his picture, we will understand that there are a huge number of inconsistencies that are subconsciously disturbing and, in general, do not receive a clear resolution. The girl that we see is a saleswoman, she must, with her physical attractiveness, make visitors stop, flirt with her and order more drinks. Meanwhile, she does not flirt with us, but looks through us. There are four bottles of champagne on the table, warm, but why not on ice? In mirror image, these bottles are not on the same edge of the table as they are in the foreground. The glass with roses is seen from a different angle from which all the other objects on the table are seen. And the girl in the mirror does not look exactly like the girl who looks at us: she is stouter, she has more rounded shapes, she leaned towards the visitor. In general, she behaves as the one we are looking at should behave.

Ilya Doronchenkov

Feminist criticism drew attention to the fact that the girl with her outlines resembles a bottle of champagne standing on the counter. This is a well-aimed observation, but hardly exhaustive: the melancholy of the picture, the psychological isolation of the heroine oppose a straightforward interpretation.

“These optical plot and psychological mysteries of the picture, which seem to have no definite answer, make us approach it again and again each time and ask these questions, subconsciously saturated with that feeling of beautiful, sad, tragic, everyday modern life, which Baudelaire dreamed of and which forever left Manet before us."

Ilya Doronchenkov

The painting "Morning of the Streltsy Execution" was painted by V. Surikov in 1881. In it, he first turned to the genre that is the essence of his painting - the image of the Russian people at bright, turning points in history.

The canvas describes the events that took place in Moscow in 1698, in the era of Peter I, when the Streltsy rebellion was brutally suppressed, and the archers were executed. The artist carefully examined eyewitness accounts, but depicted the event in accordance with his understanding of its historical meaning.

On the canvas, we see not the execution itself, but minutes full of enormous psychological stress before the inevitable execution. The action takes place in Moscow on Red Square, against the backdrop of St. Basil's Cathedral.

Early morning, the fog has not yet cleared. In the center of the composition are two heroes - Tsar Peter sitting on a horse and a red-bearded archer in a red cap. Sagittarius is bound, his legs are chained in stocks, but he has not resigned himself to his fate. Angrily, with fierce malice, he looks at Peter. We see the same irreconcilable look in Peter.

Other characters are shown in the same emotional and expressive way. The soldiers had already dragged the first condemned man to the gallows. Like a hunted animal, a black-bearded archer looks around. The look of the gray-haired archer is insane - the horror of what will happen now has clouded his mind. Sagittarius, standing on a cart, bowed, saying goodbye to the people. The young wife of the archer desperately screams, the old mother powerlessly sank to the ground.

The tragedy of what is happening emphasizes the heavy, dark color of the canvas. Skillfully building a composition, the painter skillfully creates the impression of a huge crowd, full of emotions, energy and movement. With love and attention, Surikov on the canvas treats the smallest details that characterize the historical era.

The painting "Morning of the Streltsy Fabric" was solved by Surikov as a folk drama. He told us about the people, their power, anger and suffering in an era full of difficulties and contradictions.

In addition to the description of the painting by V. I. Surikov “Morning of the Streltsy Execution”, our website has collected many other descriptions of paintings by various artists, which can be used both in preparation for writing an essay on a painting, and simply for a more complete acquaintance with the work of famous masters of the past .

|

In 1877, Surikov was taken completely on his own, without anyone's financial assistance, for his first large painting, Morning of the Streltsy Execution. The execution of archers took place in Moscow in 1698. The diary of the secretary of the Austrian Embassy Korb, an eyewitness to this event, served as the artist's main source of factual information. However, Surikov changed a lot in accordance with his understanding of the significance of the event.

With deep artistic and psychological calculation, he depicted not the execution itself, but the minutes preceding it. This made it possible to present in the picture each face in a state of the highest tension, further enhanced by psychological contrasts. Behind the back of the red-bearded archer - "evil, recalcitrant", in which "the flame of rebellion burns" (the words of N. M. Shchekotov), - stands a mother crushed by grief, mourning her son doomed to execution. Next to the black-bearded archer is his young wife, who is trying to bring him out of his state of gloomy stupor. Strong old man with a lush mop gray hair put his hand on the head of his daughter, who is sobbing, buried in his knees. Again and again a strong contrast of hopeless thought and immediate feeling. The archer standing on the cart, who is already being hurried by the soldier, abruptly turned away from Peter and bowed low before the people, saying goodbye and asking for forgiveness from him. Here and there, the blue uniforms of the Transfiguration flicker. There is neither malice nor bitterness in their faces, but rather a hidden sympathy for the archers. In the distance are curious and indifferent spectators.

But Peter sees and passionately experiences everything. The viewer finds him by following the direction of the gaze of the red-bearded archer. He is on horseback, surrounded by close boyars and foreigners. "His face is terrible." He is the embodiment of wrathful power. With a merciless look, Peter looks at the archers, as if they were the remnants of a hated past.

However, the artist pushed the king into the depths of the picture. The people became the main protagonist. The essence of the canvas is to show that extraordinary, superhuman courage, that undefeated spiritual strength that archers are endowed with, ready to face death. These are truly monumental characters in their indestructible integrity. In the images of archers created by Surikov, the viewer gets to know the mighty forces of the people, manifesting themselves in a tragic situation. The image of an agitated crowd of people, in which every face is noticeable and meaningful - that was the special concern of the artist. “I imagined all the people how worried he was. Like the noise of many waters, ”Surikov later said.

Groups consisting of archers and their families occupy the foreground of the picture. Their grief is depicted in vivid and varied features - wives and mothers, daughters and sons are completely captured by it. Grief destroyed their thoughts, crushed their will. Above this turbulent sea, the figures of the archers themselves rise like unshakable cliffs. They went through the horrors of torture. The inexorable course of events turned them into the main characters of the historical drama. The last minutes of their lives are running out. But in none of them is there even a shadow of repentance or hesitation. The cause to which they gave their lives put them above personal interests and even the interests of the family.