Spain. The rise of Spain and the beginning of its decline New and recent history

Charles V spent his life on campaigns and almost never visited Spain. Wars with the Turks, who attacked the Spanish state from the south and the possessions of the Austrian Habsburgs from the southeast, wars with France due to dominance in Europe and especially in Italy, wars with his own subjects - the Protestant princes in Germany - occupied his entire reign. The grandiose plan to create a world Catholic empire collapsed, despite Charles's numerous military and foreign policy successes. In 1555, Charles V abdicated the throne and handed over Spain, along with the Netherlands, colonies and Italian possessions, to his son Philip II (1555-1598).

Philip was not a significant person. Poorly educated, narrow-minded, petty and greedy, extremely persistent in pursuing his goals, the new king was deeply convinced of the steadfastness of his power and the principles on which this power rested - Catholicism and absolutism. Sullen and silent, this clerk on the throne spent his entire life locked in his chambers. It seemed to him that the papers and instructions were enough to know everything and manage everything. Like a spider in a dark corner, he weaved the invisible threads of his politics. But these threads were torn by the touch of the fresh wind of a stormy and restless time: his armies were often beaten, his fleets sank, and he sadly admitted that “the heretical spirit promotes trade and prosperity.” This did not stop him from declaring: “I prefer not to have subjects at all than to have heretics as such.”

Feudal-Catholic reaction was raging in the country; the highest judicial power in religious matters was concentrated in the hands of the Inquisition.

Leaving the old residences of the Spanish kings of Toledo and Valladolid, Philip II set up his capital in the small town of Madrid, on the deserted and barren Castilian plateau. Not far from Madrid, a grandiose monastery arose, which was also a palace-burial vault - El Escorial. Severe measures were taken against the Moriscos, many of whom continued to practice the faith of their fathers in secret. The Inquisition fell especially fiercely on them, forcing them to abandon their previous customs and language. At the beginning of his reign, Philip II issued a number of laws that intensified persecution. The Moriscos, driven to despair, rebelled in 1568 under the slogan of preserving the caliphate. Only with great difficulty did the government manage to suppress the uprising in 1571. In the cities and villages of the Moriscos, the entire male population was exterminated, women and children were sold into slavery. The surviving Moriscos were expelled to the barren regions of Castile, doomed to hunger and vagrancy. The Castilian authorities mercilessly persecuted the Moriscos, and the Inquisition burned “apostates from the true faith” in droves.

The brutal oppression of the peasants and the general deterioration of the economic situation of the country caused repeated peasant uprisings, of which the most powerful was the uprising in Aragon in 1585. The policy of shameless robbery of the Netherlands and a sharp increase in religious and political persecution led in the 60s of the 16th century. to the uprising in the Netherlands, which developed into a bourgeois revolution and a war of liberation against Spain.

The economic decline of Spain in the second half of the 16th and 17th centuries.

In the middle of the XVI - XVII centuries. Spain entered a period of prolonged economic decline, which first affected agriculture, then industry and trade. Speaking about the reasons for the decline of agriculture and the ruin of the peasants, sources invariably emphasize three of them: the severity of taxes, the existence of maximum prices for bread and the abuses of the Place. The country was experiencing an acute shortage of food, which further inflated prices.

A significant part of the noble estates enjoyed the right of primogeniture; they were inherited only by the eldest son and were inalienable, that is, they could not be mortgaged or sold for debts. Church lands and the possessions of spiritual knightly orders were also inalienable. In the 16th century the right of primogeniture extended to the possessions of the burghers. The existence of majorates removed a significant part of the land from circulation, which hampered the development of capitalist tendencies in agriculture.

While agricultural decline and grain plantings declined throughout the country, industries associated with colonial trade flourished. The country imported a significant portion of its grain consumption from abroad. At the height of the Dutch Revolution and the religious wars in France, real famine began in many areas of Spain due to the cessation of grain imports. Philip II was forced to allow even Dutch merchants who brought grain from the Baltic ports into the country.

At the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th century. economic decline affected all sectors of the country's economy. Precious metals brought from the New World largely fell into the hands of the nobles, and therefore the latter lost interest in the economic development of their country. This determined the decline of not only agriculture, but also industry, and primarily textile production.

By the end of the century, against the background of the progressive decline of agriculture and industry, only colonial trade, of which Seville still had a monopoly. Its highest rise dates back to the last decade of the 16th century. and by the first decade of the 17th century. However, since Spanish merchants traded mainly in foreign-made goods, gold and silver coming from America hardly stayed in Spain. Everything went to other countries in payment for goods that were supplied to Spain itself and its colonies, and were also spent on the maintenance of troops. Spanish iron, smelted on charcoal, was replaced on the European market by cheaper Swedish, English and Lorraine iron, in the production of which coal began to be used. Spain now began to import metal products and weapons from Italy and German cities.

Northern cities were deprived of the right to trade with the colonies; their ships were entrusted only with guarding caravans heading to and from the colonies, which led to the decline of shipbuilding, especially after the Netherlands rebelled and trade along the Baltic Sea sharply declined. The death of the “Invincible Armada” (1588), which included many ships from the northern regions, dealt a heavy blow. The population of Spain increasingly flocked to the south of the country and emigrated to the colonies.

The state of the Spanish nobility seemed to do everything to disrupt the trade and industry of their country. Enormous sums were spent on military enterprises and the army, taxes increased, and public debt grew uncontrollably.

Even under Charles V, the Spanish monarchy made large loans from foreign bankers, the Fuggers. At the end of the 16th century, more than half of the treasury's expenses came from paying interest on the national debt. Philip II declared state bankruptcy several times, ruining his creditors, the government lost credit and, in order to borrow new amounts, had to provide Genoese, German and other bankers with the right to collect taxes in individual regions and other sources of income, which further increased the leakage of precious metals from Spain .

The huge funds received from the robbery of the colonies were not used to create capitalist forms of economy, but were spent on unproductive consumption of the feudal class. In the middle of the century, 70% of all income from the post treasury came from the metropolis and 30% came from the colonies. By 1584, the ratio had changed: income from the metropolis amounted to 30%, and from the colonies - 70%. The gold of America, flowing through Spain, became the most important lever of primitive accumulation in other countries (and primarily in the Netherlands) and significantly accelerated the development of the capitalist structure in the bowels of feudal society there.

If the bourgeoisie not only did not strengthen, but was completely ruined by the middle of the 17th century, then the Spanish nobility, having received new sources of income, strengthened economically and politically.

As the trade and industrial activity of cities declined, internal exchange decreased, communication between residents of different provinces weakened, and trade routes became empty. The weakening of economic ties exposed the old feudal characteristics of each region, and the medieval separatism of the cities and provinces of the country was resurrected.

Under the current conditions, Spain did not develop a single national language; separate ethnic groups still remained: Catalans, Galicians and Basques spoke their own languages, different from the Castilian dialect, which formed the basis of literary Spanish. Unlike other European states, the absolute monarchy in Spain did not play a progressive role and was unable to provide true centralization.

Foreign policy of Philip II.

The decline soon became evident in Spanish foreign policy. Even before ascending the Spanish throne, Philip II was married to the English Queen Mary Tudor. Charles V, who arranged this marriage, dreamed not only of restoring Catholicism in England, but also, by uniting the forces of Spain and England, to continue the policy of creating a worldwide Catholic monarchy. In 1558, Mary died, and the marriage proposal made by Philip to the new Queen Elizabeth was rejected, which was dictated by political considerations. England, not without reason, saw Spain as its most dangerous rival at sea. Taking advantage of the revolution and the war of independence in the Netherlands, England tried in every possible way to ensure its interests here to the detriment of the Spanish ones, not stopping at open armed intervention. English corsairs and admirals robbed Spanish ships returning from America with a cargo of precious metals and blocked trade in the northern cities of Spain.

After the death of the last representative of the reigning dynasty of Portugal in 1581, the Portuguese Cortes proclaimed Philip II their king. Together with Portugal, the Portuguese colonies in the East and West Indies also came under Spanish rule. Reinforced by new resources, Philip II began to support Catholic circles in England that were intriguing against Queen Elizabeth and promoting a Catholic, the Scottish Queen Mary Stuart, to the throne instead of her. But in 1587, the plot against Elizabeth was discovered, and Mary was beheaded. England sent a squadron to Cadiz under the command of Admiral Drake, who, breaking into the port, destroyed the Spanish ships (1587). This event marked the beginning of an open struggle between Spain and England. Spain began to equip a huge squadron to fight England. The “Invincible Armada,” as the Spanish squadron was called, sailed from La Coruña to the shores of England at the end of June 1588. This enterprise ended in disaster. The death of the "Invincible Armada" was a terrible blow to the prestige of Spain and undermined its naval power.

Failure did not prevent Spain from making another political mistake - intervening in the civil war that was raging in France. This intervention did not lead to an increase in Spanish influence in France, nor to any other positive results for Spain. With the victory of Henry IV of Bourbon in the war, the Spanish cause was finally lost.

By the end of his reign, Philip II had to admit that almost all his extensive plans had failed, and the naval power of Spain had been broken. The northern provinces of the Netherlands broke away from Spain. The state treasury was empty. The country was experiencing a severe economic decline.

Spain at the beginning of the 17th century.

With accession to the throne Philip III (1598-1621) The long agony of the once powerful Spanish state begins. The poor and destitute country was ruled by the king's favorite, the Duke of Lerma. The Madrid court amazed contemporaries with its pomp and extravagance. Treasury revenues were declining, fewer and fewer galleons loaded with precious metals arrived from the American colonies, but this cargo often became the prey of English and Dutch pirates or fell into the hands of bankers and moneylenders, who lent money to the Spanish treasury at huge interest rates.

Expulsion of the Moriscos.

In 1609, an edict was issued according to which the Moriscos were to be expelled from the country. Within a few days, under pain of death, they had to board ships and go to Barbary (North Africa), carrying with them only what they could carry in their hands. On the way to the ports, many refugees were robbed and killed. In the mountainous regions, the Moriscos resisted, which accelerated the tragic outcome. By 1610, over 100 thousand people were evicted from Valencia. The Moriscos of Aragon, Murcia, Andalusia and other provinces suffered the same fate. In total, about 300 thousand people were expelled. Many became victims of the Inquisition and died during the expulsion.

Spain and its productive forces were dealt another blow, accelerating its further economic decline.

Foreign policy of Spain in the first half of the 17th century.

Despite the poverty and desolation of the country, the Spanish monarchy retained its inherited claims to play a leading role in European affairs. The collapse of all the aggressive plans of Philip II did not sober up his successor. When Philip III came to the throne, the war in Europe was still ongoing. England acted in alliance with Holland against the Habsburgs. Holland defended its independence from the Spanish monarchy with arms in hand.

The Spanish governors in the Southern Netherlands did not have sufficient military forces and tried to make peace with England and Holland, but this attempt was thwarted due to the excessive claims of the Spanish side.

Queen Elizabeth I of England died in 1603. Her successor, James I Stuart, radically changed England's foreign policy. Spanish diplomacy managed to draw the English king into the orbit of Spanish foreign policy. But that didn't help either. In the war with Holland, Spain could not achieve decisive success. The commander-in-chief of the Spanish army, the energetic and talented commander Spinola, could not achieve anything in conditions of complete depletion of the treasury. The most tragic thing for the Spanish government was that the Dutch intercepted Spanish ships from the Azores and waged a war with Spanish funds. Spain was forced to conclude a truce with Holland for a period of 12 years.

After accession to the throne Philip IV (1621-1665) Spain was still ruled by the favorites; The only new thing was that Lerma was replaced by the energetic Count Olivares. However, he could not change anything - the forces of Spain were already exhausted. The reign of Philip IV marked the final decline in Spain's international prestige. In 1635, when France directly intervened in the Thirty Years, Spanish troops suffered frequent defeats. In 1638, Richelieu decided to strike Spain on its own territory: French troops captured Roussillon and subsequently invaded the northern provinces of Spain.

Deposition of Portugal.

After Portugal joined the Spanish monarchy, its ancient liberties were left intact: Philip II sought not to irritate his new subjects. The situation changed for the worse under his successors, when Portugal became the object of the same merciless exploitation as the other possessions of the Spanish monarchy. Spain was unable to hold on to the Portuguese colonies, which passed into Dutch hands. Cadiz attracted Lisbon's trade, and the Castilian tax system was introduced in Portugal. The silent discontent growing in wide circles of Portuguese society became clear in 1637; this first uprising was quickly suppressed. However, the idea of setting aside Portugal and declaring its independence did not disappear. One of the descendants of the previous dynasty was nominated as a candidate for the throne. On December 1, 1640, having captured the palace in Lisbon, the conspirators arrested the Spanish viceroy and proclaimed her king. Joan IV of Braganza.

Textbook: chapters 4, 8::: History of the Middle Ages: Early modern times

Chapter 8.

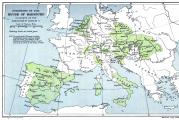

After the end of the Reconquista in 1492, the entire Iberian Peninsula, with the exception of Portugal, was united under the rule of the Spanish kings. The Spanish monarchs also owned Sardinia, Sicily, the Balearic Islands, the Kingdom of Naples and Navarre.

In 1516, after the death of Ferdinand of Aragon, Charles I ascended the Spanish throne. On his mother’s side, he was the grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella, and on his father’s side, he was the grandson of Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg. From his father and grandfather, Charles I inherited the Habsburg possessions in Germany, the Netherlands and lands in South America. In 1519, he achieved his election to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation and became Emperor Charles V. Contemporaries, not without reason, said that in his domain “the sun never sets.” However, the unification of vast territories under the rule of the Spanish crown by no means completed the process of economic and political consolidation. The Aragonese and Castilian kingdoms, connected only by a dynastic union, remained politically divided throughout the 16th century: they retained their class-representative institutions - the Cortes, their legislation and judicial system. Castilian troops could not enter the lands of Aragon, and the latter was not obliged to defend the lands of Castile in the event of war. Within the Kingdom of Aragon itself, its main parts (especially Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and Navarre) also retained significant political independence.

The fragmentation of the Spanish state was also manifested in the fact that there was no single political center; the royal court moved around the country, most often stopping in Valladolid. Only in 1605 did Madrid become the official capital of Spain.

Even more significant was the economic disunity of the country: individual regions differed sharply in the level of socio-economic development and had little connection with each other. This was largely facilitated by geographical conditions: mountainous landscape, lack of navigable rivers through which communication between the north and south of the country would be possible. The northern regions - Galicia, Asturias, the Basque Country - had almost no connection with the center of the peninsula. They conducted brisk trade with England, France and the Netherlands through the port cities of Bilbao, La Coruña, San Sebastian and Bayonne. Some areas of Old Castile and Leon gravitated towards this area, the most important economic center of which was the city of Burgos. The southeast of the country, especially Catalonia and Valencia, were closely connected with Mediterranean trade - there was a noticeable concentration of merchant capital here. The interior provinces of the Castilian kingdom gravitated towards Toledo, which for ancient times was a major center of crafts and trade.

The aggravation of the situation in the country at the beginning of the reign of Charles V.

The young king Charles I (1516 - 1555) was brought up in the Netherlands before ascending the throne. He spoke Spanish poorly, and his retinue and entourage consisted mainly of Flemings. In the early years, Charles ruled Spain from the Netherlands. His election to the imperial throne of the Holy Roman Empire, his journey to Germany and the expenses of his coronation required enormous funds, which placed a heavy burden on the Castilian treasury.

Seeking to create a “world empire,” Charles V, from the first years of his reign, viewed Spain primarily as a source of financial and human resources for pursuing imperial policy in Europe. The king's widespread involvement of Flemish confidants in the state apparatus, absolutist claims were accompanied by a systematic violation of the customs and liberties of Spanish cities and the rights of the Cortes, which caused discontent among wide sections of the burghers and artisans. The policy of Charles V, directed against the highest nobility, gave rise to mute protest, which at times grew into open discontent. In the first quarter of the 16th century. the activities of opposition forces concentrated around the issue of forced loans, which the king often resorted to from the first years of his reign.

In 1518, in order to pay off his creditors - the German bankers Fuggers - Charles V managed with great difficulty to obtain a huge subsidy from the Castilian Cortes, but this money was quickly spent. In 1519, in order to receive a new loan, the king was forced to accept the conditions put forward by the Cortes, among which was the requirement that the king not leave Spain, not appoint foreigners to government positions, and not delegate the collection of taxes to them. However, immediately after receiving the money, the king left Spain, appointing the Fleming Cardinal Adrian of Utrecht as governor.

Revolt of the urban communes of Castile (comuneros).

The king's violation of the signed agreement was the signal for an uprising of urban communes against royal power, called the "revolt of the communes" (1520-1522). After the king's departure, when the deputies of the Cortes, who had shown excessive compliance, returned to their cities, they were met with general indignation. In Segovia, artisans—clothmakers, day laborers, washers, and wool carders—revolted. One of the main demands of the rebel cities was to prohibit the import of woolen fabrics from the Netherlands into the country.

At the first stage (May-October 1520), the Comuneros movement was characterized by an alliance between the nobility and the cities. This is explained by the fact that the separatist aspirations of the nobility found support among part of the patriciate and burghers, who spoke out in defense of the medieval liberties of the cities against the absolutist tendencies of royal power. However, the union of the nobility and the cities turned out to be fragile, since their interests were largely opposed. There was a stubborn struggle between cities and grandees for the lands that were at the disposal of urban communities. Despite this, at the first stage there was a unification of all anti-absolutist forces.

At first, the movement was led by the city of Toledo, and its main leaders, the nobles Juan de Padilla and Pedro Lazo de la Vega, came from here. An attempt was made to unite all the rebel cities. Their representatives gathered in Avila, along with the townspeople there were many nobles, as well as representatives of the clergy and people of liberal professions. However, the most active role was played by artisans and people from the urban lower classes. Thus, the representative from Seville was a weaver, from Salamanca a furrier, and from Medina del Campo a clothier. In the summer of 1520, the armed forces of the rebels, led by Juan de Padilla, united within the framework of the Holy Junta. The cities refused to obey the royal viceroy and prohibited his armed forces from entering their territory.

As events developed, the program of the Comuneros movement became more specific, acquiring an anti-noble orientation, but it was not openly directed against royal power as such. The cities demanded the return of the crown lands seized by the grandees to the treasury and their payment of church tithes. They hoped that these measures would improve the financial position of the state and lead to a weakening of the tax burden, which fell heavily on the tax-paying class. However, many of the demands reflected the separatist orientation of the movement, the desire to restore medieval urban privileges (limiting the power of the royal administration in cities, restoring urban armed groups, etc.).

In the spring and summer of 1520, almost the entire country came under the control of the Junta. The Cardinal Viceroy, in constant fear, wrote to Charles V that “there is not a single village in Castile that would not join the rebels.” Charles V ordered the demands of some cities to be met in order to split the movement.

In the fall of 1520, 15 cities abandoned the uprising; their representatives, meeting in Seville, adopted a document on renunciation of the struggle, which clearly showed the patriciate’s fear of the movement of the urban lower classes. In the autumn of the same year, the cardinal-vicar began open military action against the rebels.

At the second stage (1521-1522), the program put forward by the rebels continued to be refined and refined. In the new document “99 Articles” (1521), demands appeared for the independence of the deputies of the Cortes from royal power, for their right to meet every three years, regardless of the will of the monarch, and for the prohibition of the sale of government positions. One can identify a number of demands openly directed against the nobility: to close the access of nobles to municipal positions, to impose taxes on the nobility, to eliminate their “harmful” privileges.

As the movement deepened, its orientation against the nobility began to clearly manifest itself. The rebel cities were joined by wide sections of the Castilian peasantry, who suffered from the tyranny of the grandees on the captured domain lands. Peasants destroyed estates and destroyed castles and palaces of the nobility. In April 1521, the Junta declared its support for the peasant movement directed against the grandees as enemies of the kingdom.

These events contributed to further divisions in the camp of the rebels; the nobles and nobles openly went over to the camp of the enemies of the movement. Only a small group of nobles remained in the Junta; the middle strata of the townspeople began to play the main role in it. Taking advantage of the hostility between the nobility and the cities, the Cardinal Viceroy's troops went on the offensive and defeated the troops of Juan de Padilla at the Battle of Villalar (1522). The leaders of the movement were captured and beheaded. For some time, Toledo held out, where Juan de Padilla’s wife, Maria Pacheco, operated. Despite the famine and epidemic, the rebels held firm. Maria Pacheco hoped for help from the French king Francis I, but in the end she was forced to seek salvation in flight.

In October 1522, Charles V returned to the country at the head of a detachment of mercenaries, but by this time the movement had already been suppressed.

Simultaneously with the uprising of the Castilian communeros, fighting broke out in Valencia and on the island of Mallorca. The reasons for the uprising were basically the same as in Castile, but the situation here was aggravated by the fact that city magistrates in many cities were even more dependent on the grandees, who turned them into an instrument of their reactionary policies.

However, as the uprising of the cities developed and deepened, the burghers betrayed him. Fearing that his interests would also be affected, in Valencia the leaders of the burghers persuaded some of the rebels to capitulate to the viceroy's troops, who approached the walls of the city. The resistance of supporters of continuing the struggle was broken, and their leaders were executed.

The Comuneros movement was a very complex social phenomenon. In the first quarter of the 16th century. The burghers in Spain have not yet reached the stage of development when they could already exchange urban liberties to satisfy their interests as the emerging bourgeois class. An important role in the movement was played by the urban lower classes, politically weak and poorly organized. In the uprisings in Castile, Valencia and Majorca, the Spanish burghers had neither a program capable of uniting, at least temporarily, the masses, nor the desire to wage a decisive struggle against feudalism as a whole.

The Comuneros movement demonstrated the desire of the burghers to maintain and even increase their influence in the political life of the country in the traditional way - by conserving urban liberties. At the second stage of the Comuneros uprising, the anti-feudal movement of the urban plebs and peasantry reached significant proportions, but under those conditions it could not be successful.

The defeat of the Comuneros uprising had negative consequences for the further development of Spain. The peasantry of Castile was given full power to the grandees, who had come to terms with royal absolutism; the townspeople's movement was crushed; a heavy blow was dealt to the nascent bourgeoisie; the suppression of the movement of the urban lower classes left cities defenseless against increasing tax oppression. From now on, not only the village, but also the city was plundered by the Spanish nobility.

Economic development of Spain in the 16th century.

The most populous part of Spain was Castile, where 3/4 of the population of the Iberian Peninsula lived. As in the rest of the country, land in Castile was in the hands of the crown, the nobility, the Catholic Church and spiritual knightly orders. The bulk of Castilian peasants enjoyed personal freedom. They held the lands of spiritual and secular feudal lords in hereditary use, paying a monetary qualification for them. In the most favorable conditions were the peasant colonists of New Castile and Granada, who settled on lands conquered from the Moors. Not only did they enjoy personal freedom, but their communities enjoyed privileges and liberties similar to those enjoyed by the Castilian cities. This situation changed after the defeat of the Comuneros revolt.

The socio-economic system of Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia differed sharply from the system of Castile. Here and in the 16th century. The most brutal forms of feudal dependence were preserved. The feudal lords inherited the property of the peasants, interfered in their personal lives, could subject them to corporal punishment and even put them to death.

The most oppressed and powerless part of the peasants and urban population of Spain were the Moriscos - descendants of the Moors who were forcibly converted to Christianity. They lived mainly in Granada, Andalusia and Valencia, as well as in rural areas of Aragon and Castile, were subject to heavy taxes in favor of the church and state, and were constantly under the supervision of the Inquisition. Despite persecution, the hardworking Moriscos have long grown such valuable crops as olives, rice, grapes, sugar cane, and mulberry trees. In the south they created a perfect irrigation system, thanks to which they received high yields of grain, vegetables and fruits.

For many centuries, transhumance sheep breeding was an important branch of agriculture in Castile. The bulk of the sheep flocks belonged to a privileged noble corporation - Mesta, which enjoyed special patronage from the royal power.

Twice a year, in spring and autumn, thousands of sheep were driven from; north to south of the peninsula and back along wide roads laid through cultivated fields, vineyards, olive groves. Tens of thousands of sheep, moving across the country, caused enormous damage to agriculture. Under pain of severe punishment, the rural population was forbidden to fence their fields from passing herds. Back in the 15th century. Mesta received the right to graze their flocks on the pastures of rural and urban communities, to take a perpetual lease of any piece of land if the sheep grazed on it for one season. The place enjoyed enormous influence in the country, since the largest herds belonged to the representatives of the highest Castilian nobility united in it. They achieved at the beginning of the 16th century. confirmation of all previous privileges of this corporation.

In the first quarter of the 16th century. Due to the rapid development of production in cities and the growing demand of the colonies for food in Spain, there was a slight increase in agriculture. Sources indicate an expansion of cultivated areas around large cities (Burgos, Medina del Campo, Valladolid, Seville). The trend towards intensification was most pronounced in the wine industry. However, increasing production to meet the demands of an increased market required significant funds, which was only possible for the wealthy, extremely small stratum of peasants in Spain. Most of them were forced to resort to loans from moneylenders and wealthy townspeople on the security of their holdings with the obligation to pay annual interest for several generations (super-qualification). This circumstance, together with the increase in state taxes, led to an increase in the debt of the bulk of the peasants, to their loss of land and their transformation into farm laborers or vagabonds.

The entire economic and political structure of Spain, where the leading role belonged to the nobility and the Catholic Church, hindered the progressive development of the economy.

The tax system in Spain also hampered the development of early capitalist elements in the country's economy. The most hated tax was alcabala - a 10% tax on every trade transaction; In addition, there were a huge number of permanent and emergency taxes, the size of which throughout the 16th century. increased all the time, absorbing up to 50% of the income of the peasant and artisan. The difficult situation of the peasants was aggravated by all kinds of government duties (transportation of goods for the royal court and troops, soldiers' quarters, food supplies for the army, etc.).

Spain was the first country to experience the impact of the price revolution. From 1503 to 1650, over 180 tons of gold and 16.8 thousand tons of silver were imported here, mined by the labor of the enslaved population of the colonies and looted by the conquistadors. The influx of cheap precious metal was the main reason for the increase in prices in European countries. In Spain, prices have increased 3.5 - 4 times.

Already in the first quarter of the 16th century. There was an increase in prices for basic necessities, and above all for bread. It would seem that this circumstance should have contributed to the growth of agricultural marketability. However, the system of taxes (maximum prices for grain) established in 1503 artificially kept prices for bread low, while other products quickly became more expensive. This led to a reduction in grain crops and a sharp drop in grain production in the mid-16th century. Starting from the 30s, most regions of the country imported bread from France and Sicily; imported bread was not subject to the tax law and was sold 2-2.5 times more expensive than grain produced by Spanish peasants.

The conquest of the colonies and the unprecedented expansion of colonial trade contributed to the rise of handicraft production in the cities of Spain and the emergence of individual elements of manufacturing production, especially in cloth making. In its main centers - Segovia, Toledo, Seville, Cuenca - manufactories arose. A large number of spinners and weavers in the cities and surrounding areas worked for the buyers. At the beginning of the 17th century. the large workshops of Segovia numbered several hundred hired workers.

Since Arab times, Spanish silk fabrics, famous for their high quality, brightness and color fastness, have enjoyed great popularity in Europe. The main centers of silk production were Seville, Toledo, Cordoba, Granada and Valencia. Expensive silk fabrics were little consumed on the domestic market and were mainly exported, as were brocade, velvet, gloves, and hats made in the southern cities. At the same time, coarse, cheap woolen and linen fabrics were imported into Spain from the Netherlands and England.

Metallurgy was an important branch of the economy with the beginnings of manufacturing. The northern regions of Spain, along with Sweden and Central Germany, occupied an important place in metal production in Europe. On the basis of the ore mined here, the production of bladed weapons and firearms, various metal products developed in the 16th century. the production of muskets and artillery pieces arose. In addition to metallurgy, shipbuilding and fishing were developed. The main port in trade with Northern Europe was Bilbao, which in terms of equipment and cargo turnover surpassed Seville until the middle of the 16th century. The northern regions actively participated in the export trade of wool, coming from all regions of the country to the city of Burgos. Around the Burgos-Bilbao axis there was a lively economic activity related to Spain's trade with Europe, and primarily with the Netherlands. Another old economic center of Spain was the Toledo region. The city itself was famous for the production of cloth, silk fabrics, the production of weapons and leather processing.

From the second quarter of the 16th century, in connection with the expansion of colonial trade, the rise of Seville began. In the city and its surroundings, manufactories for the production of cloth and ceramic products arose, the production of silk fabrics and the processing of raw silk developed, shipbuilding and industries related to equipping the fleet grew rapidly. The fertile valleys in the vicinity of Seville and other southern cities turned into continuous vineyards and olive groves.

In 1503, Seville's monopoly on trade with the colonies was established and the Seville Chamber of Commerce was created, which exercised control over the export of goods from Spain to the colonies and the import of goods from the New World, mainly consisting of gold and silver bars. All goods intended for export and import were carefully registered by officials and were subject to duties in favor of the treasury. Wine and olive oil became the main Spanish exports to America. Investing money in colonial trade gave very great benefits (the profit here was much higher than in other industries). In addition to the Seville merchants, merchants from Burgos, Segovia, and Toledo took part in colonial trade. A significant part of merchants and artisans moved to Seville from other regions of Spain.

The population of Seville doubled between 1530 and 1594. The number of banks and merchant companies increased. At the same time, this meant the actual deprivation of other areas of the opportunity to trade with the colonies, since due to the lack of water and convenient land routes, transporting goods to Seville from the north was very expensive. The monopoly of Seville provided the treasury with huge revenues, but it had a detrimental effect on the economic situation of other parts of the country. The role of the northern regions, which had convenient access to the Atlantic Ocean, was reduced only to the protection of flotillas heading to the colonies, which led their economy to decline at the end of the 16th century.

The most important center of internal trade and credit and financial operations in the 16th century. the city of Medina del Campo remained. Annual autumn and spring fairs attracted merchants here not only from all over Spain, but also from all European countries. Here settlements were made for the largest foreign trade transactions, agreements were concluded on loans and supplies of goods to European countries and colonies.

Thus, in the first half of the 16th century. A favorable environment has been created in Spain for the development of industry and trade. The colonies required a large amount of goods, and the huge funds that came to Spain from the 20s of the 16th century. as a result of the robbery of America, created opportunities for capital accumulation. This gave impetus to the economic development of the country. However, both in agriculture and in industry and trade, the sprouts of new, progressive economic relations met strong resistance from the conservative layers of feudal society. The development of the main branch of Spanish industry - the production of woolen fabrics - was hampered by the export of a significant part of the wool to the Netherlands. In vain, Spanish cities demanded to limit the export of raw materials in order to lower their price on the domestic market. Wool production was in the hands of the Spanish nobility, who did not want to lose their income and, instead of reducing wool exports, sought the publication of laws allowing the import of foreign cloth.

Despite the economic growth of the first half of the 16th century, Spain remained generally an agrarian country with an underdeveloped internal market; certain areas were locally closed economically.

Political system.

During the reign of Charles V and Philip II (1555-1598), central power was strengthened, but the Spanish state was politically a motley conglomerate of disunited territories. The administration of individual parts of the country reproduced the order that had developed in the Aragon-Castilian kingdom itself, which formed the political core of the Spanish monarchy. At the head of the state was the king, who headed the Castilian Council; There was also an Aragonese Council that governed Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia. Other councils were in charge of territories outside the peninsula: the Council of Flanders, the Italian Council, the Council of the Indies; These areas were governed by viceroys, appointed, as a rule, from representatives of the highest Castilian nobility.

Strengthening absolutist tendencies in the 16th - first half of the 17th centuries. led to the decline of the Cortes. Already by the first quarter of the 16th century. their role was reduced exclusively to voting new taxes and loans to the king. Only representatives of cities were increasingly invited to their meetings. Since 1538, the nobility and clergy were not officially represented in the Cortes. At the same time, in connection with the massive relocation of nobles to the cities, a fierce struggle broke out between the burghers and the nobility for participation in city government. As a result, the nobles secured the right to occupy half of all positions in municipal bodies.

Increasingly, nobles acted as representatives of cities in the Cortes, which indicated the strengthening of their political influence. True, the nobles often sold their municipal positions to wealthy townspeople, many of whom were even residents of these places, or rented them out.

The further decline of the Cortes was accompanied in the middle of the 17th century by the deprivation of their right to vote taxes, which was transferred to city councils, after which the Cortes stopped convening.

In the XVI - early XVII centuries. large cities, despite significant advances in industrial development, largely retained their medieval appearance. These were urban communes where the patriciate and nobles were in power. Many city residents who had fairly high incomes purchased “hidalgia” for money, which freed them from paying taxes, which fell heavily on the middle and lower strata of the urban population.

Throughout the period, the strong power of the large feudal nobility remained in many areas. Spiritual and secular feudal lords had judicial power not only in rural areas, but also in cities, where entire neighborhoods, and sometimes cities with the entire district, were under their jurisdiction. Many of them received from the king the right to collect state taxes, which further increased their political and administrative power.

The beginning of the decline of Spain. Philip II.

Charles V spent his life on campaigns and almost never visited Spain. Wars with the Turks, who attacked the Spanish state from the south and the possessions of the Austrian Habsburgs from the southeast, wars with France due to dominance in Europe and especially in Italy, wars with his own subjects - the Protestant princes in Germany - occupied his entire reign. The grandiose plan to create a world Catholic empire collapsed, despite Charles’s numerous military and foreign political successes.

In 1555, Charles V abdicated the throne, transferring Spain, the Netherlands, the colonies in America and the Italian possessions to his eldest son Philip II. In addition to the legitimate heir, Charles V had two illegitimate children: Margaret of Parma, the future ruler of the Netherlands, and Don Juan of Austria, a famous political and military figure, the winner of the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto (1571).

The future King Philip II grew up without a father, since Charles V had not been to Spain for almost 20 years. The heir grew up gloomy and withdrawn. Like his father, Philip II took a pragmatic view of marriage, often repeating the words of Charles V: “Royal marriages are not for family happiness, but for the continuation of the dynasty.” The first son of Philip II from his marriage to Maria of Portugal - Don Carlos - turned out to be physically and mentally disabled. Experiencing mortal fear of his father, he prepared to secretly flee to the Netherlands. Rumors of this prompted Philip II to take his son into custody, where he soon died.

Purely political calculations dictated the second marriage of 27-year-old Philip II with the 43-year-old Catholic Queen of England Mary Tudor. Philip II hoped to unite the efforts of the two Catholic powers in the fight against the Reformation. Four years later, Mary Tudor died without leaving an heir. Philip II's bid for the hand of Elizabeth I, the Protestant Queen of England, was rejected.

Philip II was married 4 times, but of his 8 children only two survived. Only in his marriage to Anna of Austria did he have a son, the future heir to the throne, Philip III. not distinguished by either health or ability to govern the state.

Leaving the old residences of the Spanish kings of Toledo and Valla Dolid, Philip II established his capital in the small town of Madrid on the deserted and barren Castilian plateau. Not far from Madrid, a grandiose monastery arose, which was at the same time a palace-burial vault - El Escorial.

Severe measures were taken against the Moriscos, many of whom continued to practice the faith of their fathers in secret. The Inquisition fell upon them, forcing them to abandon their previous customs and language. At the beginning of his reign, Philip II issued a number of laws that intensified their persecution. The Moriscos, driven to despair, rebelled in 1568 under the slogan of preserving the caliphate.

With great difficulty, the government managed to suppress the uprising in 1571. In the cities and villages of the Moriscos, the entire male population was exterminated, women and children were sold into slavery. The surviving Moriscos were expelled to the barren regions of Castile, doomed to hunger and vagrancy. The Castilian authorities mercilessly persecuted the Moriscos, and the Inquisition burned hundreds of “apostates from the true faith.”

The brutal oppression of the peasants and the general deterioration of the economic situation of the country caused repeated peasant uprisings, of which the strongest was the uprising in Aragon in 1585. The policy of shameless robbery of the Netherlands and a sharp increase in religious and political persecution led in the 60s of the 16th century. to the uprising in the Netherlands, which developed into a war of liberation against Spain (see Chapter 9).

The economic decline of Spain in the second half of the 16th – 17th centuries.

Beginning in the mid-16th century, Spain entered a period of prolonged economic decline, which first affected agriculture, then industry and trade. Speaking about the reasons for the decline of agriculture and the ruin of the peasants, sources invariably emphasize three of them: the severity of taxes, the existence of maximum prices for bread and the abuses of the Place. Peasants were driven from their lands, communities were deprived of their pastures and meadows, this led to the decline of livestock farming and a reduction in crops. The country was experiencing an acute shortage of food, which further inflated prices. The main reason for the rise in prices of goods was not the increase in the amount of money in circulation, but the fall in the value of gold and silver due to the decrease in the cost of mining precious metals in the New World.

In the second half of the 16th century. In Spain, the concentration of land ownership in the hands of the largest feudal lords continued to increase. A significant part of the noble estates enjoyed the right of primogeniture; they were inherited by the eldest son and were inalienable, that is, they could not be mortgaged or sold for debts. Church lands and the possessions of spiritual knightly orders were also inalienable. Despite the significant debt of the highest aristocracy in the 16th-17th centuries, the nobility retained its land holdings and even increased them by purchasing domain lands sold by the crown. The new owners eliminated the rights of communities and cities to pastures, seized communal lands and plots of those peasants whose rights were not properly formalized. In the 16th century the right of primogeniture extended to the possessions of the burghers. The existence of majorates removed a significant part of the land from circulation, which hampered the development of capitalist tendencies in agriculture.

The country experienced an intensive process of expropriation of the peasantry, which led to a reduction in the rural population in the northern and central regions of the country. The petitions of the Cortes constantly speak of villages where there were only a few inhabitants left, forced to bear the exorbitant burden of taxes. So, in one of the villages near the city of Toro, there were only three residents left who sold the bells and sacred vessels from the local church to pay taxes. Many peasants did not have tools or draft animals and sold standing grain long before harvest. In Castile there was a significant stratification of the peasantry. In many villages in the Toledo region, 60 to 85% of the peasants were day laborers who systematically sold their labor.

At the same time, against the backdrop of the decline of small peasant farming, large commercial farms arose, based on the use of short-term rentals and hired labor and largely export-oriented. These trends are especially characteristic of the south of the country. Almost all of Extremadura ended up in the hands of the two largest magnates; the best lands of Andalusia were divided between several lords. Vast expanses of land here were occupied by vineyards and olive groves. In the wine industry, hired labor was used especially intensively, and there was a transition from hereditary to short-term rental. While agricultural decline and grain plantings declined throughout the country, industries associated with colonial trade flourished. The country imported a significant portion of its grain consumption from abroad.

At the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th century. economic decline affected all sectors of the country's economy. Precious metals brought from the New World largely fell into the hands of the nobles, and therefore the latter lost interest in economic activity. This determined the decline of not only agriculture, but also industry, and primarily textile production.

Manufactures began to emerge in Spain in the first half of the 16th century, but they were few in number and did not receive further development. The largest center of manufacturing production was Segovia. Already in 1573, the Cortes complained about the decline in the production of woolen fabrics in Toledo, Segovia, Que and other cities. Such complaints are understandable, since, despite the growing demand of the American market, due to rising prices for raw materials and agricultural products, and rising wages, fabrics made abroad from Spanish wool were cheaper than Spanish ones.

The production of the main type of raw material - wool - was in the hands of the nobility, who did not want to lose their income received from high prices for wool in Spain itself and abroad. Despite repeated requests from cities to reduce wool exports, it constantly increased and almost quadrupled from 1512 to 1610. Under these conditions, expensive Spanish fabrics could not withstand competition with cheaper foreign ones, and Spanish industry lost markets in Europe, in the colonies, and even in its own country. Trading companies of Seville since the middle of the 16th century. began to increasingly resort to replacing expensive Spanish products with cheaper goods exported from the Netherlands, France, and England. The fact that until the end of the 60s, i.e., also had a negative impact on Spanish manufacturing. During the period of its formation, when it especially needed protection from foreign competition, the commercial and industrial Netherlands were under the rule of Spain. These areas were considered by the Spanish monarchy as part of the Spanish state. The duties on wool imported there, although increased in 1558, were two times lower than usual, and the import of finished Flemish cloth was carried out on more favorable terms than from other countries. All this had disastrous consequences for Spanish manufacturing: the merchants withdrew their capital from manufacturing production, since participation in the colonial trade in foreign goods promised them great profits.

By the end of the century, against the background of the progressive decline of agriculture and industry, only colonial trade continued to flourish, the monopoly of which continued to belong to Seville. Its highest rise dates back to the last decade of the 16th century. and by the first decade of the 17th century. However, since Spanish merchants traded mainly in foreign-made goods, gold and silver coming from America almost did not stay in Spain, but flowed to other countries in payment for goods that were supplied to Spain itself and its colonies, and were also spent on the maintenance of troops. Spanish iron, smelted on charcoal, was replaced on the European market by cheaper Swedish, English and Lorraine iron, in the production of which coal began to be used. Spain now began to import metal products and weapons from Italy and German cities.

The state spent enormous sums on military enterprises and the army, taxes increased, and public debt grew uncontrollably. Even under Charles V, the Spanish monarchy made large loans from foreign bankers the Fuggers, to whom, in order to repay the debt, they were given income from the lands of the spiritual knightly orders of Sant Iago, Calatrava and Alcantara, whose master was the King of Spain. Then the Fuggers acquired the richest mercury-zinc mines of Almaden. At the end of the 16th century. More than half of the treasury's expenditures came from paying interest on the national debt. Philip II declared state bankruptcy several times, ruining his creditors; the government lost credit and, in order to borrow new amounts, had to provide Genoese, German and other bankers with the right to collect taxes from certain regions and other sources of income.

Outstanding Spanish economist of the second half of the 16th century. Thomas Mercado wrote about the dominance of foreigners in the country’s economy: “No, they could not, the Spaniards could not calmly look at the foreigners prospering on their land; the best possessions, the richest majorates, all the income of the king and nobles are in their hands.” Spain was one of the first countries to embark on the path of primitive accumulation, but the specific conditions of socio-economic development prevented it from following the path of capitalist development. The huge funds received from the robbery of the colony were not used to create new forms of economy, but were spent on unproductive consumption of the feudal class. In the middle of the 16th century. 70% of all treasury revenues came from the metropolis and 30% was given to the colonies. By 1584, the ratio had changed: income from the metropolis amounted to 30%, and from the colonies - 70%. American gold, flowing through Spain, became the most important lever of primitive accumulation in other countries (primarily in the Netherlands) and significantly accelerated the development of early capitalist forms of economy there. In Spain itself, which began in the 16th century. the process of capitalist development came to a halt. The decomposition of feudal forms in industry and agriculture was not accompanied by the formation of an early capitalist structure.

Spanish absolutism.

The absolute monarchy in Spain had a very unique character. Centralized and subordinate to the individual will of the monarch or his all-powerful temporary workers, the state apparatus had a significant degree of independence. In its policy, Spanish absolutism was guided by the interests of the nobility and the church. This became especially clear during the period of the economic decline of Spain that followed in the second half of the 16th century. As the trade and industrial activity of cities declined, internal exchange decreased, communication between residents of different provinces weakened, and trade routes became empty. The weakening of economic ties exposed the old feudal characteristics of each region, and the medieval separatism of the cities and provinces of the country was resurrected.

Under the current conditions, separate ethnic groups continued to exist in Spain: Catalans, Galicians and Basques spoke their own languages, different from the Castilian dialect, which formed the basis of literary Spanish. Unlike other European states, the absolute monarchy in Spain did not play a progressive role and was unable to provide true centralization.

Foreign policy of Philip II.

After the death of Mary Tudor and the accession of the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I to the English throne, Charles V's hopes of creating a worldwide Catholic power by uniting the forces of the Spanish monarchy and Catholic England were dashed. Relations between Spain and England worsened, which, not without reason, saw Spain as its main rival at sea and in the struggle for the seizure of colonies in the Western Hemisphere. Taking advantage of the war of independence in the Netherlands, England tried in every possible way to ensure its interests here, not stopping at armed intervention.

English corsairs robbed Spanish ships returning from America with a cargo of precious metals and blocked trade in the northern cities of Spain.

Spanish absolutism set itself the task of crushing this “heretical and robber nest”, and if successful, taking possession of England. The task began to seem quite feasible after Portugal was annexed to Spain. After the death of the last representative of the reigning dynasty in 1581, the Portuguese Cortes proclaimed Philip II their king. Together with Portugal, the Portuguese colonies in the East and West Indies, including Brazil, also came under Spanish rule. Reinforced by new resources, Philip II began to support Catholic circles in England that were intriguing against Queen Elizabeth and promoting a Catholic, the Scottish Queen Mary Stuart, to the throne instead of her. But in 1587, a conspiracy against Elizabeth was discovered, and Mary was beheaded. England sent a squadron to Cadiz under the command of Admiral Drake, who, breaking into the port, destroyed the Spanish ships (1587). This event served as the beginning of an open struggle between Spain and England. Spain began to equip a huge squadron to fight England. “The Invincible Armada” was the name of the Spanish squadron that sailed from La Coruña to the shores of England at the end of June 1588, but the enterprise ended in disaster. The death of the "Invincible Armada" was a terrible blow to the prestige of Spain and undermined its naval power.

Failure did not prevent Spain from making another political mistake - intervening in the civil war that was raging in France (see Chapter 12). This intervention did not lead to an increase in Spanish influence in France, nor to any other positive results for Spain.

Spain's fight against the Turks brought more victorious laurels. The Turkish danger looming over Europe became especially noticeable when the Turks captured most of Hungary and the Turkish fleet began to threaten Italy. In 1564 the Turks blockaded Malta. Only with great difficulty was it possible to hold the island.

In 1571, the combined Spanish-Venetian fleet under the command of Don Juan of Austria inflicted a crushing defeat on the Turkish fleet in the Gulf of Lepanto. This victory stopped further maritime expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean. Don Juan pursued far-reaching goals: to seize Turkish possessions in the eastern Mediterranean, recapture Constantinople and restore the Byzantine Empire. The ambitious plans of his half-brother alarmed Philip I. He refused him military and financial support. Tunisia, captured by Don Juan, again passed to the Turks.

By the end of his reign, Philip II had to admit that almost all his extensive plans had failed, and the naval power of Spain had been broken. The northern provinces of the Netherlands broke away from Spain. The state treasury was empty, the country was experiencing a severe economic decline. The entire life of Philip II was devoted to the implementation of his father's main idea - the creation of a worldwide Catholic power. But all the intricacies of his foreign policy collapsed, his armies suffered defeats; the flotillas sank. At the end of his life, he had to admit that “the heretical spirit promotes trade and prosperity,” but despite this he persistently repeated: “I prefer not to have subjects at all than to have heretics as such.”

Spain at the beginning of the 17th century.

With the accession of Philip III (1598-1621) to the throne, the long agony of the once powerful Spanish state began. The niche and destitute country was ruled by the king's favorite Duke of Lerma. The Madrid court amazed contemporaries with its pomp and extravagance, while the masses were exhausted under the unbearable burden of taxes and endless extortions. Even the obedient Cortes, to whom the king turned for new subsidies, were forced to declare that there was nothing to pay, since the country was completely ruined, trade was killed by the alcabala, industry was in decline, and the cities were empty. Treasury revenues decreased, fewer and fewer galleons loaded with precious metals arrived from the American colonies, but this cargo often became the prey of English and Dutch pirates or fell into the hands of bankers and moneylenders who lent money to the Spanish treasury at huge interest rates.

The reactionary nature of Spanish absolutism was expressed in many of its actions. One striking example is the expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain. In 1609, an edict was issued according to which the Moriscos were subject to eviction from the country. Within a few days, under pain of death, they had to board ships and go to Barbary (North Africa), carrying only what they could carry in their hands. On the way to the ports, many refugees were robbed and killed. In the mountainous regions, the Moriscos resisted, which accelerated the tragic outcome. By 1610, over 100 thousand people were evicted from Valencia. The Moriscos of Aragon, Murcia, Andalusia and other provinces suffered the same fate. In total, about 300 thousand people were expelled. Many became victims of the Inquisition or died during the expulsion.

Foreign policy of Spain in the first half of the 17th century.

Despite the poverty and desolation of the country, the Spanish monarchy retained its inherited claims to play a leading role in European affairs. The collapse of all the aggressive plans of Philip II did not sober up his successor. When Philip III came to the throne, the war in Europe was still ongoing. England acted in alliance with Holland against the Habsburgs. Holland defended its independence from the Spanish monarchy with arms in hand.

The Spanish governors in the Southern Netherlands did not have sufficient military forces and tried to make peace with England and Holland, but this attempt was thwarted due to the excessive claims of the Spanish side.

Queen Elizabeth I of England died in 1603. Her successor, James I Stuart, radically changed England's foreign policy. Spanish diplomacy managed to draw the English king into the orbit of Spanish foreign policy. But that didn't help either. In the war with Holland, Spain could not achieve decisive success. The commander-in-chief of the Spanish army, the energetic and talented commander Spinola, could not achieve anything in conditions of complete depletion of the treasury. The most tragic thing for the Spanish government was that the Dutch intercepted Spanish ships from the Azores and waged a war with Spanish funds. Spain was forced to conclude a truce with Holland for a period of 12 years.

After the accession of Philip IV (1621-1665), Spain was still ruled by favorites; Lerma was replaced by the energetic Count Olivares. However, he could not change anything. The reign of Philip IV marked the final decline in Spain's international prestige. In 1635, when France directly intervened in the Thirty Years' War (see Chapter 17), Spanish troops suffered frequent defeats. In 1638, Richelieu decided to strike Spain on its own territory: French troops captured Roussillon and subsequently invaded the northern provinces of Spain. But there they encountered resistance from the people.

By the 40s of the 17th century. the country was completely exhausted. The constant strain on finances, the extortion of taxes and duties, the rule of an arrogant, idle nobility and fanatical clergy, the decline of agriculture, industry and trade - all this gave rise to widespread discontent among the masses. Soon this dissatisfaction burst out.

Deposition of Portugal.

After Portugal joined the Spanish monarchy, its ancient liberties were left intact: Philip II sought not to irritate his new subjects. The situation changed for the worse under his successors, when Portugal became the object of the same merciless exploitation as the other possessions of the Spanish monarchy. Spain was unable to hold on to the Portuguese colonies, which passed into Dutch hands. Cadiz attracted Lisbon's trade, and the Castilian tax system was introduced in Portugal. The silent discontent growing in wide circles of Portuguese society became clear in 1637.

The first uprising was quickly suppressed. However, the idea of setting aside Portugal and declaring its independence did not disappear. One of the descendants of the previous dynasty was nominated as a candidate for the throne. The conspirators included the Archbishop of Lisbon, representatives of the Portuguese nobility, and wealthy citizens. On December 1, 1640, having captured the palace in Lisbon, the conspirators arrested the Spanish viceroy and proclaimed Joan IV of Braganza king.

Popular movements in Spain in the first half of the 17th century.

The reactionary policies of Spanish absolutism led to a number of powerful popular movements in Spain and its possessions. In these movements, the struggle against seigneurial oppression in the countryside and the actions of the urban lower classes were often aimed at preserving medieval liberties and privileges. In addition, separatist revolts of the feudal nobility and the ruling elite of the cities often enjoyed military support from abroad and were intertwined with the struggle of the peasantry and urban plebs. This created a complex balance of social forces.

In the 30-40s of the 17th century. Along with the revolts of the nobility in Aragon and Andalusia, powerful popular uprisings broke out in Catalonia and Vizcaya. The uprising in Catalonia began in the summer of 1640. The immediate reason for it was the violence and looting of Spanish troops intended to wage war with France and stationed in Catalonia in violation of its liberties and privileges.

The rebels were divided into two camps from the very beginning. The first were the feudal-separatist layers of the Catalan nobility and the patrician-burgher elite of the cities. Their program was the creation of an autonomous state under the protectorate of France and the preservation of traditional liberties and privileges. In order to achieve their goals, these layers entered into an alliance with France and even went so far as to recognize Louis XIII as Count of Barcelona. The other camp included the peasantry and urban plebs of Catalonia, who made anti-feudal demands. The revolting peasants were not supported by the urban plebs of Barcelona. They killed the viceroy and many government officials. The uprising was accompanied by pogroms and looting of the houses of the city's rich. Then the nobility and the city elite called in French troops. The looting and violence of the French troops caused even greater anger among the Catalan peasants. Clashes between peasant detachments and the French began, whom they considered foreign invaders. Frightened by the growth of the peasant-plebeian movement, the nobles and urban elite of Catalonia in 1653 agreed to reconciliation with Philip V on the condition of preserving their liberties.

Culture of Spain in the 16th-17th centuries.

The unification of the country, economic growth in the first half of the 16th century, the growth of international relations and foreign trade associated with the discovery of new lands, and the developed spirit of entrepreneurship determined the high rise of Spanish culture. The heyday of the Spanish Renaissance dates back to the second half of the 16th - first decades of the 17th century.

The most important centers of education were the leading Spanish universities in Salamanca and Alcala de Henares. At the end of the 15th - first half of the 16th century. At the University of Salamanca, the humanistic direction in teaching and research prevailed. In the second half of the 16th century. Copernicus' heliocentric system was studied in the university classrooms. At the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th centuries. here the first sprouts of humanistic ideas in the field of philosophy and law arose. An important event in the country's public life were the lectures of the outstanding humanist scientist Francisco de Vitoria, dedicated to the situation of the Indians in the newly conquered lands of America. Vitoria rejected the need for forced baptism of Indians and condemned the mass extermination and enslavement of the indigenous population of the New World. Among the university's scientists, the outstanding Spanish humanist, priest Bartolomé de Las Casas, found support. As a participant in the conquest of Mexico and then a missionary, he spoke out in defense of the indigenous population, painting in his book “The True History of the Ruin of the Indies” and in other works a terrible picture of the violence and cruelty inflicted by the conquistadors. Salamanca scholars supported his project to free enslaved Indians and prohibit them from being enslaved in the future. In the debates that took place in Salamanca, in the works of scientists Las Casas, F. de Vitoria, and Domingo Soto, the idea of the equality of the Indians with the Spaniards and the unjust nature of the wars waged by the Spanish conquerors in the New World was first put forward.

The discovery of America, the “price revolution,” and the unprecedented growth of trade required the development of a number of economic problems. In search of an answer to the question of the reason for the rise in prices, the economists of Salamanca produced a number of economic studies that were important for that time on the theory of money, trade and exchange, and developed the basic principles of the policy of mercantilism. However, in Spanish conditions these ideas could not be put into practice.

The great geographical discoveries and the conquest of lands in the New World had a huge impact on the social thought of Spain, on its literature and art. This influence was reflected in the spread of humanistic utopia in the literature of the 16th century. The idea of a “golden age,” which was previously sought in antiquity, in the ideal knightly past, was now often associated with the New World; Various projects were born to create an ideal Indian-Spanish state in the newly discovered lands. Las Casas, F. de Herrera, and A. Quiroga associated the dream of reconstructing society with faith in the virtuous nature of man, in his ability to overcome obstacles to achieving the common good.

By the first half of the 16th century. refers to the activities of the outstanding Spanish humanist, theologian, anatomist and physician Miguel Servetus (1511-1553). He received a brilliant humanistic education. Servetus opposed one of the main Christian dogmas about the trinity of God in one person, and was associated with the Anabaptists. For this he was persecuted by the Inquisition, and the scientist was forced to flee to France. His book was burned. In 1553, he anonymously published a treatise, “The Restoration of Christianity,” in which he criticized not only Catholicism, but also the tenets of Calvinism. That same year, Servetus was arrested while passing through Calvinist Geneva, accused of heresy and burned at the stake.

Since the spread of Renaissance ideas in philosophical form and the development of advanced science were extremely difficult by the Catholic reaction, humanistic ideas received their most vivid embodiment in art and literature. The uniqueness of the Spanish Renaissance was that the culture of this period, more than in other countries, was associated with folk art. Outstanding masters of the Spanish Renaissance drew their inspiration from it.

For the first half of the 16th century. The widespread distribution of adventurous chivalric and pastoral novels was typical. Interest in chivalric novels was explained by the nostalgia of the impoverished hidalgo nobles for the past. At the same time, this was not a memory of the heroic exploits of the Reconquista, when knights fought for their homeland, against the enemies of their people and their king. Hero of knightly novels of the 16th century. - an adventurer who performs feats in the name of personal glory, the cult of his lady. He fights not with the enemies of his homeland, but with his rivals, wizards, monsters. This stylized literature carried the reader into unknown lands, into the world of love adventures and daring adventures in the taste of the court aristocracy.

A favorite genre of urban literature was the picaresque novel, the hero of which was a tramp, very unscrupulous in his means, achieving material well-being through trickery or arranged marriage. Particularly famous was the anonymous novel “The Life of Lazarillo of Tormes” (1554), the hero of which, as a child, was forced to leave his home, going to wander the world in search of food. He becomes a guide to a blind man, then a servant to a priest, to an impoverished hidalgo, so poor that he feeds himself from the alms that Lazarillo collects. At the end of the novel, the hero achieves material well-being through an arranged marriage. This work opened up new traditions in the genre of picaresque novel.

At the end of the 16th - first half of the 17th century. In Spain, works appeared that were included in the treasury of world literature. The palm in this regard belongs to Miguel Cervantes de Saavedra (1547-1616). Coming from an impoverished noble family, Cervantes went through a life full of hardships and adventures. Service as a secretary to the papal nuncio, a soldier (he participated in the Battle of Lepanto), a tax collector, an army supplier, and, finally, a five-year stay in captivity in Algeria introduced Cervantes to all layers of Spanish society, allowed him to deeply study its life and customs, and enriched his life experience.

He began his literary activity by composing plays, among which only the patriotic “Numancia” received wide recognition. In 1605, the first part of his great work, “The Cunning Hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha,” appeared, and in 1615, the second part. Conceived as a parody of the chivalric romances popular at the time, Don Quixote became a work that went far beyond this concept. It turned into a real encyclopedia of life at that time. The book shows all layers of Spanish society: nobles, peasants, soldiers, merchants, students, tramps.

Since ancient times, folk theaters have existed in Spain. Traveling troupes staged plays of both religious content and folk comedies and farces. Often performances took place in the open air or in the courtyards of houses. The plays of the greatest Spanish playwright Lope de Vega appeared on the popular stage for the first time.

Lope Feliz de Vega Carpio (1562-1635) was born in Madrid into a modest family of peasant origins. Having gone through a life path full of adventures, in his declining years he accepted the priesthood. Enormous literary talent, good knowledge of folk life and the historical past of his country allowed Lope de Vega to create outstanding works in all genres: poetry, drama, novel, religious mystery. He wrote about two thousand plays, of which four hundred have reached us. Like Cervantes, Lope de Vega depicts in his works, imbued with the spirit of humanism, people of the most varied social status - from kings and nobles to vagabonds and beggars. In the dramaturgy of Lope de Vega, humanistic thought was combined with the traditions of Spanish folk culture. All his life, Lope fought against the classicists from the Madrid Theater Academy, defending the right to the existence of mass folk theater as an independent genre. During the controversy, he wrote a treatise, “The New Art of Creating Comedy in Our Time,” directed against the canons of classicism.

Lope de Vega created tragedies, historical dramas, comedies of manners. His mastery of intrigue has been brought to perfection; he is considered the creator of a special genre - the “cloak and sword” comedy. He wrote over 80 plays based on subjects from Spanish history, among which stand out works dedicated to the heroic struggle of the people during the Reconquista. The people are genuine, the heroes of his works. One of his most famous dramas is “Fuente Ovejuna” (“The Sheep Spring”), which is based on a true historical fact - a peasant uprising against a cruel oppressor and rapist, the commander of the Order of Calatrava.

Followers of Lope de Vega were Tirso de Molina 0571 1648) and Caldera de la Barca (1600-1681). Tirso Molina's merit was to further improve his dramatic skills and give his works a minted form, defending the freedom of the individual and his right to enjoy life, Tirso de Molina nevertheless defended the steadfastness of the principles of the existing system and the Catholic faith. He is responsible for the creation of the first version of “Don Juan” - a theme that later received such deep development in drama and music.